Study Shows Key Molecular Differences in Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukemia Could Lead to Better Treatment

| LITTLE ROCK – A scientist at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) is among the lead authors of a study that could lead to more effective therapies for children with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

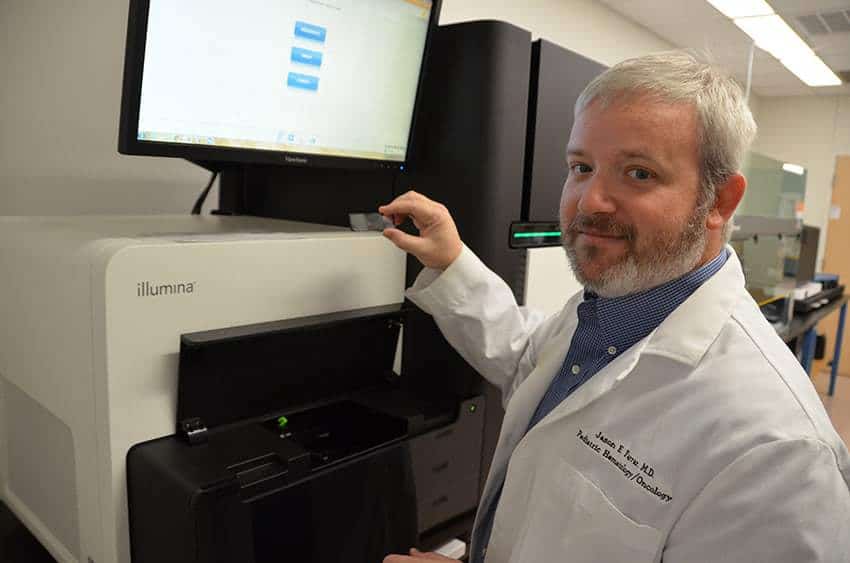

UAMS’ Jason Farrar, M.D., and collaborators at eleven other institutions published their study in the journal Nature Medicine and presented findings at the 2017 American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting (ASH) held Dec. 9-12 in Atlanta. Many of the published results were first released at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting, held in San Diego.

“Although research has made great strides in improving survival rates for children with acute lymphocytic leukemia, progress in AML, a less common less form of childhood leukemia, has lagged behind. Our research is a step forward in understanding how to better treat children with this challenging disease,” said Farrar, assistant professor in the UAMS College of Medicine Department of Pediatrics.

The study’s findings identified key differences between the molecular structure of AML in young patients as opposed to those who are older. Due to these differences, the researchers concluded that traditional therapies used to treat adults with AML are not effective for children and young adults with the same disease.

“One of our key findings is that there is a clear age continuum in the biology of AML. Because the disease develops differently in the young, middle aged and old, we know that we can’t use the previously accepted therapies that were designed for older adults and expect them to have the same outcomes for children and young adults,” Farrar said.

The study involved an analysis of the genomes of more than 1,000 AML patients treated nationwide through the Children’s Oncology Group, with ages ranging from 8 days to 29 years. Of that number, 200 had their entire genome sequenced for the study, however the group’s continuing research includes whole-genome sequencing for hundreds more participants.

Data also was gathered from about 400 of these patients to determine how their cancer cells read and interpreted the DNA changes.

“We need high-depth data on every AML patient we treat to get the best possible understanding of how this disease works at a molecular level,” Farrar said.

Most commonly diagnosed in older adults, AML starts in the bone marrow and can move quickly to the blood. According to the American Cancer Society, about 21,000 Americans are diagnosed with AML each year and about 10,600 die of it. As stated in the researchers’ paper, four out of 10 young AML patients do not survive long term.

Based on their findings, Farrar and his collaborators have already developed an improved system for determining the severity of AML in young people at the time of their diagnosis. The individual patient’s treatment is then tailored to the severity of their disease, with those who have less severe disease receiving treatment with fewer possible side effects.

This system is implemented at Seattle Children’s Hospital, where collaborator Soheil Meshinchi, M.D., of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, sees patients and will soon be integrated into national cooperative clinical trials for children and young adults with AML.

“Being able to identify whether a child has high-risk or low-risk disease is very important to their long-term outlook. For example, many of the drugs used to treat AML can cause young patients to have cardiac conditions as they age. If we can effectively treat their cancer with drugs that do not damage their heart, we definitely want to do that,” Farrar said.

Funded by the National Cancer Institute, this research effort is part of a program called the TARGET Initiative, which is focused on determining the genetic changes that drive the formation and progression of hard-to-treat childhood cancers. TARGET stands for Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments.

In addition to AML, the TARGET Initiative researchers also study acute lymphoblastic leukemia, kidney tumors, neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma.

Additional support for this study comes from the Arkansas Biosciences Institute, the Center for Translational Pediatric Research at Arkansas Children’s, Scientific Computing at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the University of Southern California’s Center for High-Performance Computing, St. Baldrick’s Foundation and the Jane Anne Nohl Hematology Research Fund.

In addition to Farrar and Meshinchi, the paper’s lead authors include Hamid Bolouri, Ph.D., and Rhonda E. Ries of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Timothy Triche Jr., M.D., Ph.D., of the Van Andel Research Institute and University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

UAMS is the state’s only health sciences university, with colleges of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Health Professions and Public Health; a graduate school; a hospital; a main campus in Little Rock; a Northwest Arkansas regional campus in Fayetteville; a statewide network of regional campuses; and eight institutes: the Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, Jackson T. Stephens Spine & Neurosciences Institute, Harvey & Bernice Jones Eye Institute, Psychiatric Research Institute, Donald W. Reynolds Institute on Aging, Translational Research Institute, Institute for Digital Health & Innovation and the Institute for Community Health Innovation. UAMS includes UAMS Health, a statewide health system that encompasses all of UAMS’ clinical enterprise. UAMS is the only adult Level 1 trauma center in the state. UAMS has 3,485 students, 915 medical residents and fellows, and seven dental residents. It is the state’s largest public employer with more than 11,000 employees, including 1,200 physicians who provide care to patients at UAMS, its regional campuses, Arkansas Children’s, the VA Medical Center and Baptist Health. Visit www.uams.edu or uamshealth.com. Find us on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), YouTube or Instagram.###