Exhibit Features History of Minority Students, Faculty at UAMS

| Numerous achievements of minorities over the past 70 years of UAMS history, as well as photographs and artifacts that tell the story of minority health care in Arkansas before the end of Jim Crow are on display in a new historical exhibit across from the College of Medicine.

The exhibit is sponsored by the UAMS Historical Research Center, which has the mission of preserving the history of UAMS and the health sciences in Arkansas.

Throughout the exhibit, specific focus is given to the career of Edith Irby Jones, M.D., the first black student since Reconstruction to earn a medical degree from a public institution in Arkansas – or anywhere in the South.

Jones graduated in 1952 from what was then the University of Arkansas School of Medicine. She was followed by Morris Andrew Jackson, M.D., and Truman Tollette, M.D., in 1954 and Willie Mott, M.D., in 1955, all of whom are also pictured in the exhibit.

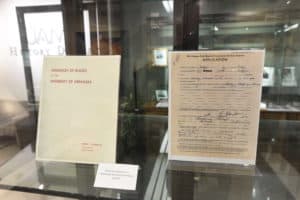

Artifacts preserved in the exhibit include guidelines that ended segregation at the University of Arkansas and an application for admission from Jones.

Jocelyn Elders, M.D., another accomplished minority alumna of UAMS and former U.S. Surgeon General under President Bill Clinton, is also noted in the exhibit, which includes a handwritten note in which she acknowledged Jones as her hero.

“I wanted to pull all these people in and tie them all in with Dr. Jones. She was the first,” said April Hughes, an administrative analyst for the Historical Research Center. Part of the UAMS Diversity Committee for 15 years, Hughes researched and led the effort to install the exhibit.

Jones is considered a trailblazer, having attended medical school as a black female at a time when women were not typically expected to pursue higher education, much less a professional degree, and blacks were still living in a segregated society. Though the integration of UAMS did not spark the chaos that erupted with the integration of Little Rock Central High School in 1957, Jones’s admission still stirred some objections.

“People did not want her here, and that’s just the bottom line. They did not want blacks, period,” said Hughes, who credits the leadership of H. Clay Chenault, M.D., dean and vice president of the School of Medicine, who fought to make sure that Jones could attend once she proved herself academically qualified. “Regardless of what some people didn’t want, it happened. She came. She stayed. She graduated.”

In addition to students, the exhibit honors groundbreaking members of faculty, past and present, including Phillip Rayford, Ph.D., the first black department chair, E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., MBA, the first black dean of the College of Medicine, and Billy Thomas, M.D., M.P.H., the first vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion and director of the UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs.

Beyond the history of UAMS, the exhibit tells the story of minority health care in Arkansas prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, when hospitals were still segregated. It includes photographs of several historical hospitals, including the Negro Infirmary and Training School, originally opened in 1913, and the United Friends of America Hospital, which opened in 1922. It also provides information on the Mosaic Templars of America, a black fraternal organization based in Little Rock that helped members of the African-American community.

The new exhibit, timed to coincide with Black History Month, will remain on display through June. The UAMS Historical Research Center encourages anyone with documents or artifacts that document the achievements of African-Americans in the medical and health sciences fields at UAMS or throughout Arkansas to contact Tim Nutt, director, at tgnutt@uams.edu or 501-686-6735.