History Professor Talks 1860 Expulsion of Free Blacks for Black History Month

| Dozens attended a celebration held to conclude Black History Month hosted by the UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs, which featured musical entertainment and a lecture.

“Given the way things are in our society, we need to become more proactive and aggressive in addressing some of the issues that go on around us,” said Billy Thomas, M.D., M.P.H., vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion, by way of welcome. “Our whole aim is to educate and change the culture.

“I remember when I was in school we studied Arkansas history, there was nothing about black people at all. Nothing,” Thomas continued. “I think it’s time for use as a society and as an academic health center to have an open and honest dialogue focusing on social justice including the past, current and long-term effects of slavery. ”

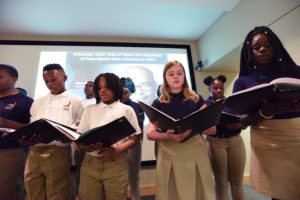

To that end, the day’s celebration featured a performance by the Forest Heights advanced choir singing arrangements of two spirituals, “Joshua Fought the Battle of Jericho” and “Go Down Moses (Tell Old Pharaoh, ‘Let My People Go’).”

Following that, featured speaker Brian Mitchell, Ph.D., an assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, presented a talk on the 1860 expulsion of free blacks from Arkansas.

“My coming to history wasn’t by accident,” Mitchell said. “My coming to history was largely because of absences. Missing information that made me question everything that was and everything I knew in my early years.”

One of those missing narratives, he emphasized, was the push by white citizens in Arkansas to remove free blacks in the late 1850s. Mitchell related how a group of prominent white citizens kept proposing measures to remove free blacks – not for anything they had done, but because their presence antagonized slaveholders.

“‘Even if they [free blacks] do nothing actively, their very existence here and their condition as freedmen, make them constant though silent preachers to the slaves those notions that they are dangerous in the last degree to us and injurious to them,’” said Mitchell, quoting an 1858 circular printed in the Arkansas Gazette. “What they’re saying is that, even if they did everything right, even if they were model citizens, because we need to keep other blacks enslaved, we cannot have these people anywhere around us.”

Mitchell related how the state ultimately passed a law exiling free blacks that went into effect Jan. 1, 1860. He talked about the research he’s done to identify who these exiled people were and where they went. Official records indicate the law affected some 600 people.

“I worked with a group of students and we decided to try to identify who these individuals were and where they ultimately found refuge. We were able to identify some 1,200 individuals who found their way to neighboring states and resided there.”

That research included the stories of people like Nathan Warrren, a prominent baker whose confections were favored by patrons among the elite of white society, many of whom claimed him as a friend and an honest man – but nevertheless pushed to have him expelled. It included Henry King, who had to sell off four lots of prime real estate on Main Street in Little Rock, which included two houses, a smokehouse, a well and fruit trees – even knowing whites would likely cheat him knowing they could simply wait for him to be forced out and buy the property at auction.

“You have to imagine for yourselves how hard it must have been for an African-American man to have acquired such a property in 1859 and then be forced to abandon it,” Mitchell said.

“I think it’s important that we discuss this particular topic, because it’s something I’ve never seen covered anywhere in Arkansas history. All of the history books that I’ve pulled up, even history books of African-American history, they only list this as a footnote, covering it in a sentence or two,” Mitchell added, concluding his lecture. “So the idea of actually giving names to people and trying to come up with definitive numbers and directions in which people went is essential to filling this gap in Arkansas history.”