View Larger Image

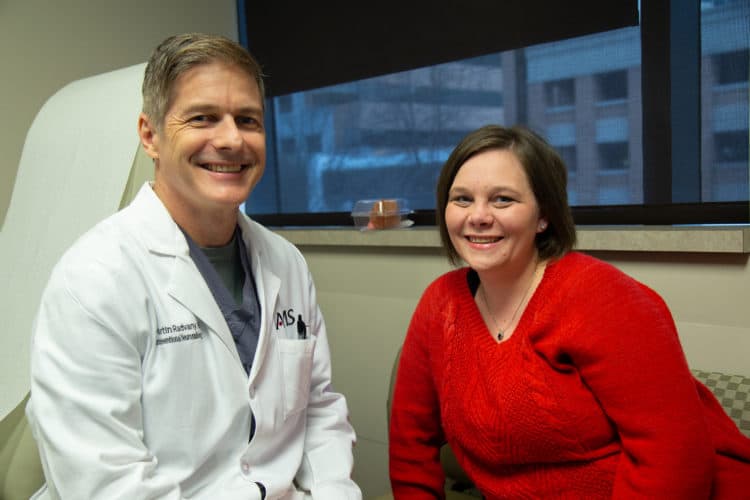

Valerie Hutchens sees Martin Radvany, M.D. for a follow-up appointment.

Physician Treats Rare Cerebrovascular Disease, Restores Patient’s Vision

| The first thing Valerie Hutchens noticed when she woke up in the recovery room after surgery was how much clearer the voices around her sounded.

“I can hear you!” she said to her surgeon, Martin Radvany, M.D., UAMS interventional neuroradiologist.

Among the myriad of symptoms Hutchens experienced with idiopathic intracranial hypertension was a constant whooshing sound with every heartbeat. PTC, also known as idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a condition that causes increased pressure in and around the brain.

PTC is part of the spectrum of cerebrovascular diseases. Because UAMS is the only Comprehensive Stroke Center in Arkansas, it has the expertise of interventional neuroradiologists, neurosurgeons and neurologists who work in teams to help take care of patients with complex diseases.

“Idiopathic just means we don’t know what causes it,” Radvany said. “The other term “pseudotumor” is because the symptoms mimic that of a brain tumor, causing increased pressure around the brain. A subset of patients with PTC have narrowing of the transverse sinuses/veins in the head.”

Hutchens, 34, lives with her husband, Zach, and 5-year-old son, Aiden, in Mansfield, Ark. She first started noticing something was off in early 2017. There were many mornings she’d wake up with a headache and didn’t want to get out of bed, but pressed through her day anyway.

“It felt like something was holding my head, constantly squeezing it,” Hutchens said. “Light bothered me. I sometimes even had to wear sunglasses inside.”

Her vision loss was subtle. At first, she noticed it taking her eyes longer to adjust to changes in light from one room to the next. In April, there were blind spots about the size of her pupil in both eyes. She scheduled an appointment with her eye doctor.

The optometrist noticed that her optic nerve was swollen so he ordered a CT scan, which ruled out a brain tumor and confirmed the PTC diagnosis.

Hutchens’ neurologist treated the PTC with lumbar punctures, also known as spinal taps. For this procedure, he inserted a needle into her back to drain the fluid buildup that caused the increased pressure. The lumbar punctures, in addition to medication, provided some relief but not for long. Eventually, Hutchens would need a lumbar puncture every two months.

“It was painful and tedious,” she said. “It required me to lay flat for half an hour with the needle in my back then lay flat for two more hours after they were done. When I got home, I’d have to stay still for two days. I had two spinal headaches from that. You haven’t had a headache until you’ve had a spinal headache.”

Hutchens asked her primary care physician to refer her to UAMS.

“I knew there was another way,” Hutchens said. “I’ve done a lot of research.”

Radvany performed a surgical procedure that permanently alleviated pressure and would prevent future fluid buildup. He inserted a catheter into a vein in her leg, then navigated it through the vessels until it reached her brain. Once there, he measured the pressure and placed a stent – a tube in the vessel to keep it from narrowing – in the area that the pressure was abnormal.

“Once the stent is established, the blood flow and pressure surrounding the brain returns to normal,” Radvany said.

Hutchens noticed she felt better immediately after her procedure.

“Not only did the whooshing sound stop, but by the time I left the hospital, I no longer needed my reading glasses.”

She did have residual swelling in her optic nerve and is seeing her ophthalmologist for monitoring and treatment.

PTC, more prominent in women, is fairly uncommon and still considered a rare condition by the National Institutes of Health.