UAMS Professor’s New Book Sheds Light on Neuroscience and the Law

| If science isn’t about the search for absolute truth but instead the search for the best possible answer, then a UAMS professor hopes he and his late co-author have found the best answers so far to questions about neuroscience and the law.

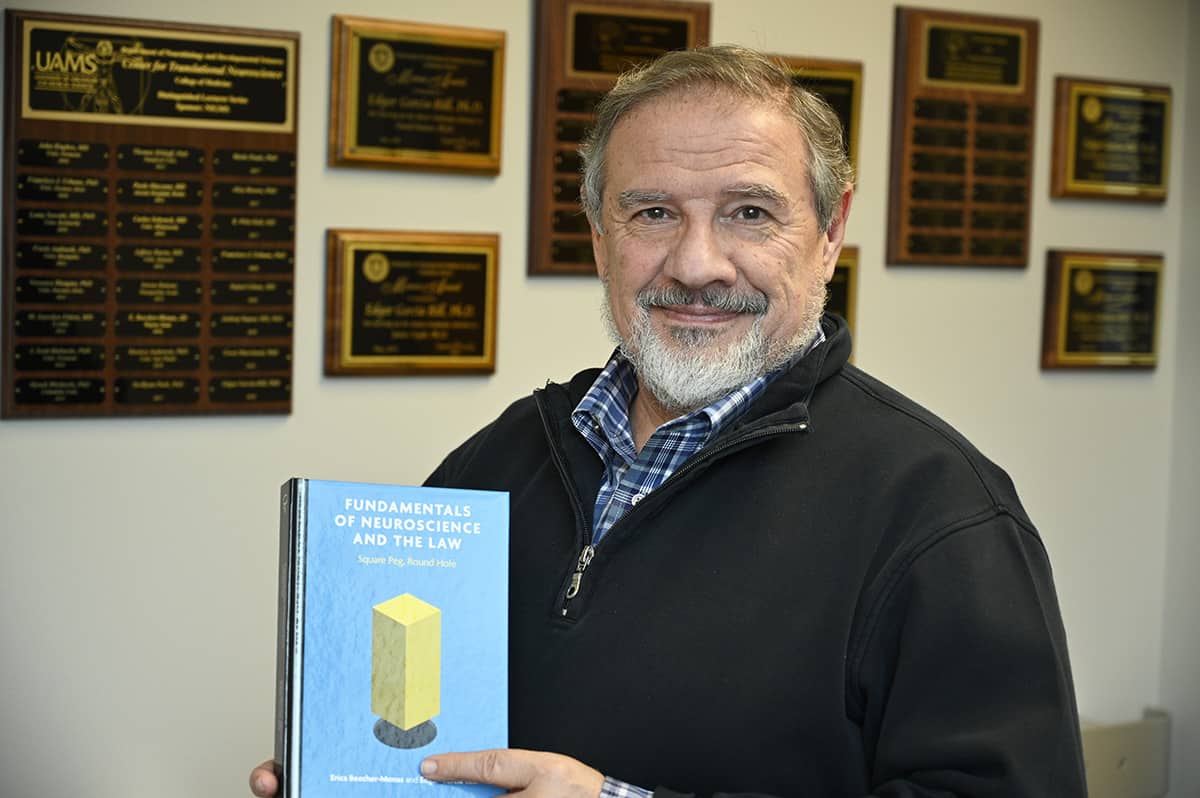

Cambridge Scholars Publishing recently released a new textbook on the subject “Fundamentals of Neuroscience and the Law,” by UAMS neurobiologist Edgar Garcia-Rill, Ph.D., and Erica Beecher-Monas, a lawyer and professor of law at Wayne State University in Detroit who died in 2017.

The book provides insights into the intersection of these two fields, addressing questions such as why courts sometimes dismiss medically sound mental health diagnoses, and how laws could be drafted to be more scientifically based.

Garcia-Rill and Beecher-Monas planned for the book to serve as a guide to law students and others seeking to understand how the greatly expanded knowledge about the brain and human behavior can be applied in court and legal processes.

The two professors over many years of collaboration wrote several articles in legal journals that make up several chapters of the new book. Together, Beecher-Monas and Garcia-Rill wanted to examine several questions relating to neuroscience and the law: how lawyers and judges could properly use expert testimony in criminal and civil cases, the role of testimony regarding mental health and the concept of “future dangerousness.”

In the 1980s, the U.S. Supreme Court established a new rule of evidence called the Daubert standard, derived from a civil case, Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc. Garcia-Rill said that standard requires an expert witness to be able to explain science and scientific evidence in an easy-to-understand way to a judge before a trial begins. That judge then can decide whether to allow the witness to give testimony that likely can also be understood by a jury.

The Supreme Court based its decision on the 20th Century philosopher, Karl Popper. Sir Karl Popper was the first speaker at the Philosophy of Science series that Dr. Garcia-Rill spearheaded at UAMS, laying the foundation for his collaboration with Beecher-Monas.

When experts gave mental health testimony in cases in which criminal defendants pleaded insanity, judges often dismissed it because they saw psychology and psychiatry as “soft sciences,” Garcia-Rill said. That attitude persisted even as diagnostic technology and neuroscientists produced harder data and harder evidence.

One important finding in recent decades was in regard to how the health of the brain as an organ might affect criminal behavior.

“For the majority of violent criminal cases where the real problem arises is with frontal lobe damage,” Garcia-Rill said. “Of all the murderers in prisons, over 80 percent had some frontal lobe damage, or they had a congenital problem there. The frontal lobes are the brakes. They keep you from impulsive actions. In addition, alcohol tends to inhibit frontal lobe function. So someone with decreased frontal lobe function who is also drinking alcohol is a recipe for disaster. That is perhaps why four out of five incidences of violence are under the influence of alcohol.”

“It’s never, ever one factor that contributes to someone committing criminal acts of violence,” he said. “There are always multiple factors we don’t know about.”

The authors also examined the concept of “future dangerousness” — the idea that understanding someone’s genetics might help predict whether they might commit crimes in the future. In the 1990s when genomics was still a new science, some legal scholars thought that might be a possibility. Garcia-Rill said while genes may play a role, that role is far from simple. Genes and behavior always are conditioned by many other factors in a person’s development and environment. Genes do not determine behavior, they just make proteins.

Regarding intent and whether someone always chooses to act or not, Garcia-Rill and Beecher-Monas give the example of someone walking along a sidewalk while in conversation yet being ‘preconscious’ of traffic and other pedestrians so as to allow for safe navigation. That is, while we are paying attention to an action, we process information to which we are not paying attention but are well aware of.

“In the same way, we are preconscious to the performance of our voluntary movements, and therefore responsible for all of our actions,” Garcia-Rill said. “And yes, free will is alive and well.”

Studies by the late researcher Benjamin Libet in the early 1980s suggested that one’s voluntary movements begin “unconsciously” because brain waves are manifested in advance of the subjective “will” to move. This led to the suggestion that there is no free will. Libet surmised that individuals still have the ability to stop actions or movements of which they are not fully conscious. This became known as “free won’t.” But in legal terms, it introduced much confusion.

“It doesn’t mean you’re not responsible,” Garcia-Rill said. “In fact, our interpretation that you are preconsciously aware and not unconscious suggests that you are indeed responsible for everything you’re doing. You’re responsible for that first drink you took at the bar. You can argue about brain damage, but the fact is you still went to the bar and that’s preconscious awareness.”

Garcia-Rill said for too long the legal community and the courts held on to concepts of the brain and mental health that dated back to the 1950s or even earlier. That’s started to change as research like his and his colleagues has become better known. He said he hopes “Fundamentals of Neuroscience and the Law” will be used by law professors and other legal educators to create greater understanding of the role science and scientific expertise can play in the justice system