Past and Future Both Part of UAMS Black History Month Celebrations

| A lecture looking backward and a panel discussion looking forward punctuated the observance of Black History Month at UAMS.

Two virtual events hosted by the diversity, inclusion and engagement subcommittee of the UAMS Division for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DDEI) highlighted the month, including a lecture by Tim Nutt, director of the UAMS Historical Research Center, called “Trailblazers: African American Health Care Leaders in Arkansas History” and a panel of Black UAMS doctors discussing the documentary Black Men in White Coats, which examines the societal barriers between Black men and medical school.

“The committee wanted to both highlight historical accomplishments of African American Arkansans and invite everyone to consider the importance of that legacy, both today and in the future,” said Odette Woods, senior director for staff diversity, equity and inclusion and the DDEI staff liaison to the committee.

Trailblazers

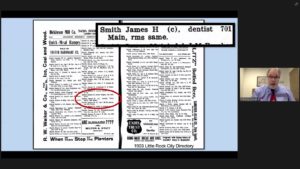

The virtual lecture, presented during the noon hour on Feb. 25, offered a deep dive into notable names across all health professions from throughout Arkansas history, starting with the multitalented James H. Smith, a dentist, inventor, artist and author who arrived in Little Rock in the 1870s and who (unusually for the time) saw both white and Black patients.

“The esteem and prominence that Dr. Smith held in Little Rock and across the South is evident in the text of his obituaries,” said Nutt, who noted Smith was also the father of internationally known composer Florence Beatrice Price, who moved to Chicago before her rise to fame. “Both statewide newspapers — the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat — as well as prominent Black newspapers around the country published extensive obituaries which noted his many accomplishments.”

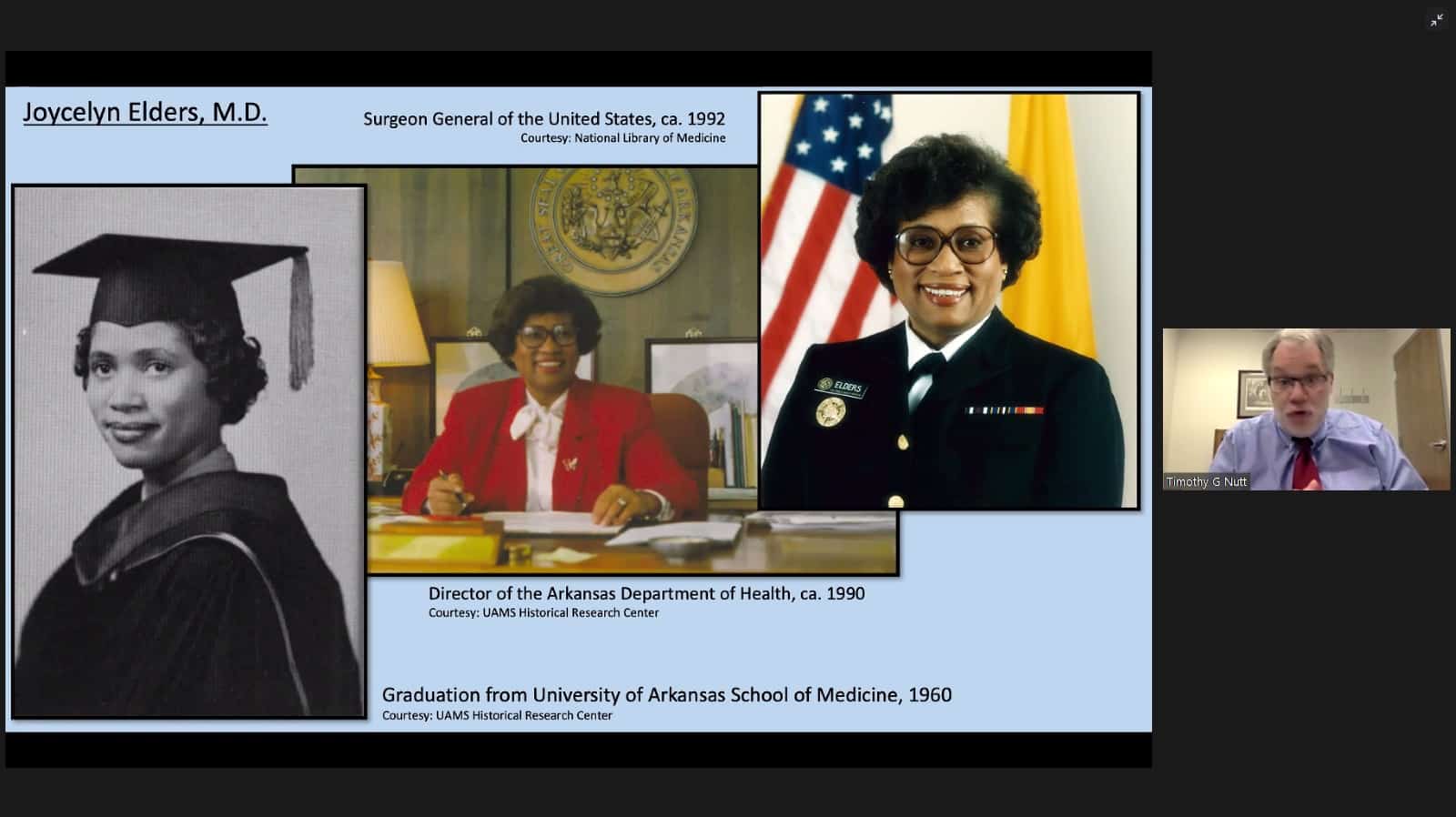

From there Nutt discussed luminaries from throughout the 19th and 20th centuries who built hospitals, opened drug stores, fought for civil rights and demolished barriers, including UAMS alumni Edith Irby Jones, M.D., the university’s first Black student and first Black graduate from a predominately white medical institution south of the Mason Dixon line, and Jocelyn Elders, M.D., who became the first Black U.S. Surgeon General. Together they established a legacy still resonant today.

“Of course, this presentation only highlights a few of the African American Arkansans who have contributed to the health sciences,” concluded Nutt. “More research and documentation needs to happen so that their histories and contributions are not lost.”

Black Men in White Coats

In addition to the historical lecture, the subcommittee arranged for all UAMS faculty, staff and students to have online access to the documentary Black Men in White Coats and then participate in a virtual panel discussion of the many issues brought up in the film.

Christian Simmons, M.D., Ph.D., participating in the online panel discussion of the documentary Black Men in White Coats.

The panel was moderated by Sharanda Williams, assistant dean for diversity and student affairs in the College of Medicine, and included: Antonio Howard, M.D.; Adam Johnson, M.D., Ph.D.; Billy Thomas, M.D., MPH; Christian Simmons, M.D., Ph.D.; and Kevin Means, M.D.; as well as Kimberlyn Blann-Anderson, DDEI’s director of student outreach and engagement.

“The film really discussed many things that I’ve lived through,” said Means, a physician since 1982 and chair of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. “They talked about your environment, even before medical school, they talked about professional isolation, some discrimination issues, the mentor issue, the pipeline issue. Many very significant issues were addressed.”

The panel discussed the film’s analysis of the lack of representation of Black male doctors and the effect that has on the aspirations of young Black men.

“I grew up in a country where all the leaders, the physicians, the professionals, they all looked just like me, and I see, looking back and having moved here, the awesome impact that’s had on my life,” said Howard, who is from Barbados and a faculty member in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. “So I appreciated that one of their ideas is to improve role modeling and selling the idea, to our young men in particular, that they can be more than society tells them — or even more than what they tell themselves — they can be.”

Thomas, a neonatologist and first vice chancellor of the UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs (now DDEI), noted the need for an educational pipeline with programs that reach all the way down to elementary school.

“At the K-6 level, that’s where a lot of these things begin,” he said of institutional barriers, whether implicit bias or racism built into environment like public schools that force students into stigmatized tracking programs. “Some students have a home environment that can pull you out of that, but a lot of them don’t.”

Johnson, an otolaryngologist, used his own lived experience as an example, noting his parents who constantly had to go to bat for him against a school system that kept trying to label him with a learning disability.

“The school tried to put me in special education,” he said. “But now I have an M.D. and a Ph.D., so I think they did pretty good.”

Panel participant Adam Johnson, M.D., Ph.D., talks about the challenges educational systems can present.

He went on to talk about his educational experiences, both positive and negative. Working in a hospital where most of the support staff were Black while most of the physicians were white, he said he was struck by a random message of support from a page operator saying the staff were all cheering for him. On the other hand, he was also confronted by patients or families who could not fathom that he was a doctor.

“I’ve been mistaken for cleanup crew or cafeteria staff, and having this white coat does not mean I’m above any of those tasks. But when trying to treat patients it can be a problem,” he said.

Simmons, a vascular surgeon, added two of his own career experiences of racism, both with patients. Once a patient simply did not want a Black man taking care of him. In another, a patient with whom he had a good rapport, was being tested for awareness and was asked who the president was.

“His response was ‘that n-word Obama,’” said Simmons. “I was very much challenged with being professional in that moment. I reminded him that I thought we had a better relationship than that, and both he and his wife apologized.”

Thomas offered hope that such incidents will become history.

“I’ve been around long enough that I’ve seen a lot of changes. I think we’ve all been confronted with someone who doesn’t want a Black doctor taking care of them,” said Thomas, noting even Black patients who’ve internalized the idea that Black doctors are not as well trained have said it to him. “But it is getting better. I think now the biggest issue is around unconscious bias, and it being hard to know where people are. That’s the troublesome thing to me.”

To that end, and in answer to a participant question, Williams noted many of the steps UAMS has taken to improve its recruitment and retention of people of color, both as employer and school. She drew attention to ongoing, institution-wide unconscious bias training for all employees, as well as growing diversity in hiring and admittance committees.

“This fall, we’re launching a post-bac program to prepare people of color who want to get into the College of Medicine to help fill those gaps,” she said.

Likewise, Blann-Anderson noted DDEI’s work on pipeline programs, which have moved online in response to the pandemic, but as a consequence have become available statewide. Covering every level of education from kindergarten to undergraduate, they help steer minority and underrepresented students into scientific and health care fields.

“We have a strong commitment to advancing Black men through our pipeline programs,” she said. “We are strongly recruiting from K-3, because even with that young age, they are thinking about what they want to be.”

View the full Black Men in White Coats panel discussion here.