Disability Awareness Means Putting People First, Expert Says

| Breaking down barriers to inclusion for people with disabilities begins by focusing on a person’s identity first, not their disability.

That was the key focus of a virtual presentation Oct. 21 to members of Team UAMS hosted by the Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DDEI) Disability subcommittee. Elizabeth Reed, the corporate diversity inclusion manager for Arkansas Rehabilitation Services, focused on the power of inclusive, “people-first” language to create a sense of belonging.

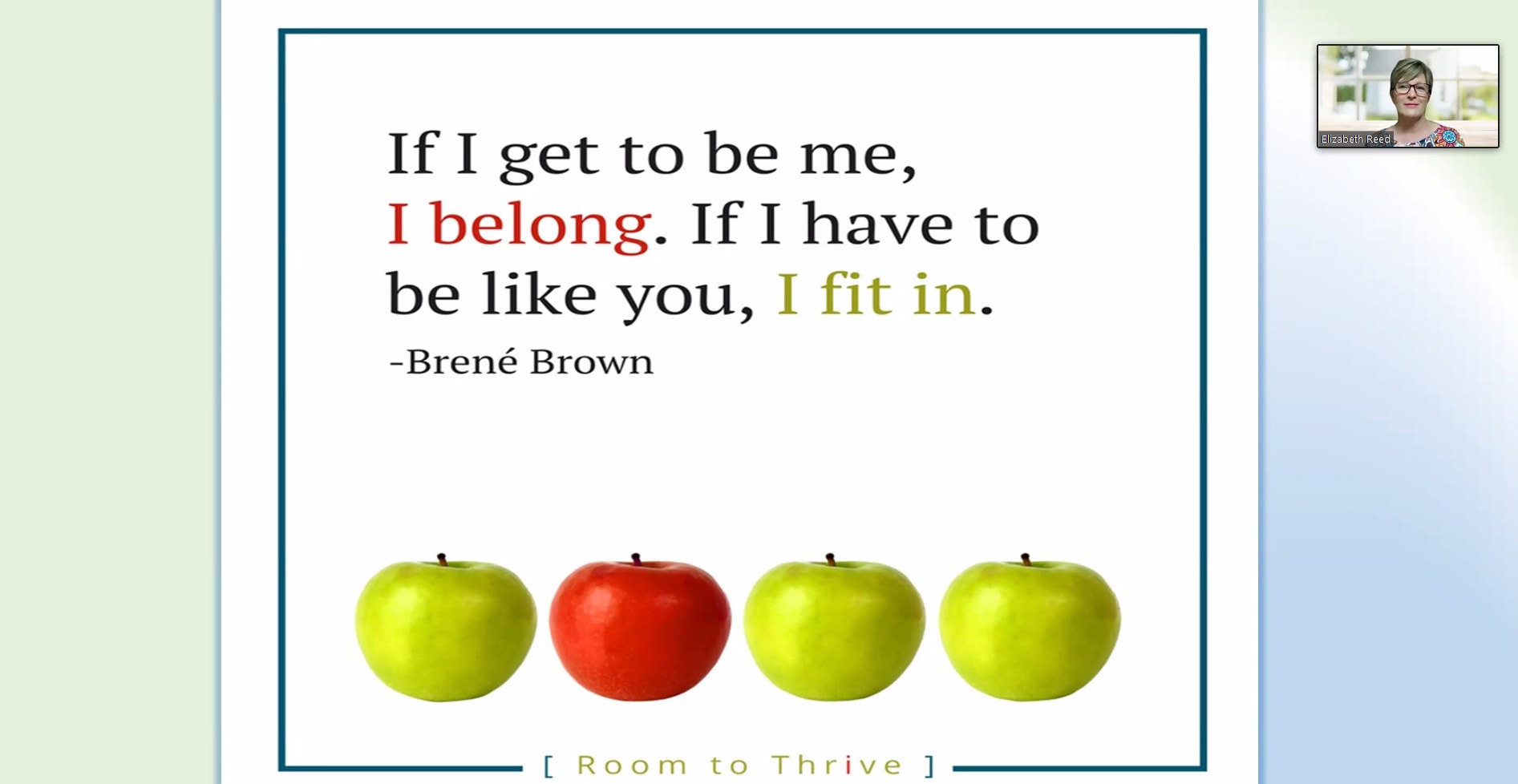

“We need to feel that sense of belonging every day, and we need to feel it at our workplace too,” Reed said. “Belonging has a strong correlation to motivation and commitment in the workplace.”

October was National Disability Employment Awareness Month, which educates about disability employment issues and celebrates individuals with disabilities in the workplace. This year’s theme was “America’s Recovery: Powered by Inclusion.”

More than 61 million adults in the United States live with a disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At least 822,145 adults in Arkansas have a disability. This is equal to 35% of all Arkansans, or 1 in 3 residents.

“For the second year, our DDEI disability subcommittee has hosted a signature event during National Disability Employment Awareness Month to bring an awareness of and sensitivity to issues related to people with disabilities,” said DDEI’s Odette Woods, senior director for staff diversity, equity and inclusion. “For the upcoming year, the subcommittee decided to focus on inclusive language, and this workshop represents our first step in bringing attention to the positive and negative use of language and its impact on building an equitable, inclusive and welcoming campus environment.”

Approximately 60 employees attended the presentation, moderated by subcommittee member Janean Hardister, in which Reed shared stories and anecdotes along with several examples of more inclusive language.

“Words are powerful,” Hardister said. “People want to be known by their name, strength, abilities, hopes and dreams, not their disability.”

Hardister advocated for using people-first language, which means putting the person first in speaking, not the disability. People-first language can be thought of as a formula, she said: someone’s name or title, followed by a verb, followed by an assistive device or disability. An example would be to say “people with disabilities” instead of “the handicapped or disabled.”

“If I use people-first language, I’m showing that person that I value them for everything they are,” Reed said. “It’s not about fluffy and flowery language and being something that we’re not. It’s about being purposeful and meaning it.”

It’s important to understand a person’s identity, and how they identify themselves, she said. Some people with disabilities identify by their disability; others do not.

Reed, who has had hearing loss throughout her life, mentioned how she would be treated differently when someone learned she had hearing loss. They would raise their voice when speaking or exaggerate their lip movements, which only aggravated the issue and prevented her ability to read lips. So, she avoided bringing up her disability.

“Know that I can do this job, not that I have a disability that says I can’t,” she said.

People with disabilities, particularly women and people of color, face longstanding gaps in employment and advancement. According to the Department of Labor, people of working age with disabilities have more than twice the unemployment rate of people without disabilities.

One of the biggest reasons people with disabilities do not ask for accommodations in the workplace is a fear of being fired, Reed said.

She encouraged workers to make sure to ask for what they need. Fostering inclusion and belonging can increase retention among all employees in the workplace because everyone feels comfortable.

“Reflect on yourself and understand that it’s okay [to mess up],” she said. “We just have to accept that and move forward.”

Reed challenged everyone to be inclusive and reach out to others.

“We’ve got to empower ourselves, and that’s what diversity and inclusion and belonging is,” she said. “It’s empowering. And if we feel empowered, nobody can defeat us.”

UAMS partners with Arkansas Rehabilitation Services and the Little Rock-based nonprofit ACCESS® on UAMS Project SEARCH, a nine-month internship program for young adults with developmental disabilities. The first of its kind in Arkansas, UAMS Project SEARCH has seen more than 82 interns achieve a 90% employment rate. The National Rehabilitation Association recently recognized UAMS for this success with its Roger Carter Award of Excellence for Large Employers.