View Larger Image

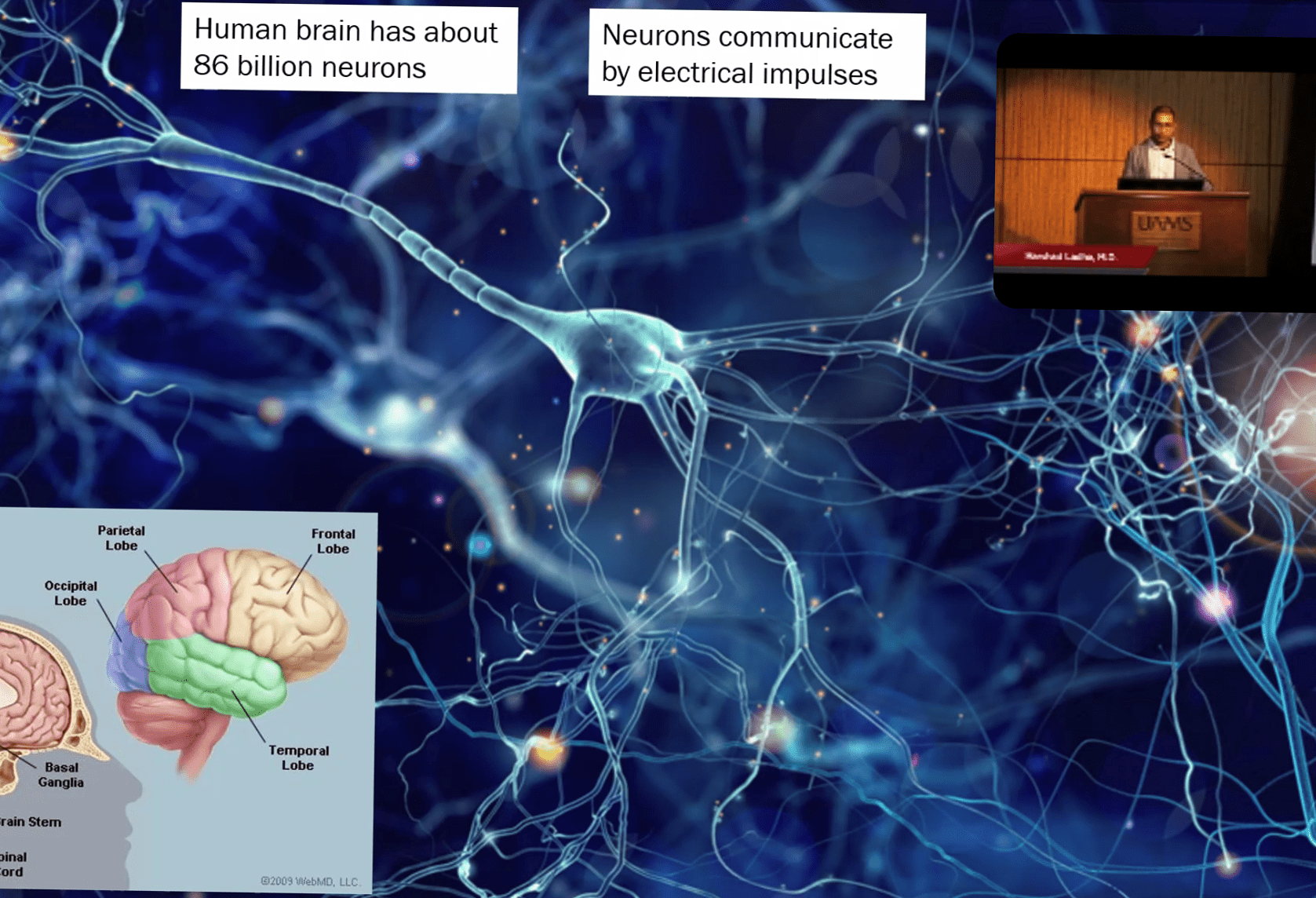

Harshad Ladha, M.D., used graphics to illustrate his presentation.

Epilepsy Experts Share Updates on Condition during UAMS Symposium

| Six multidisciplinary experts on epilepsy shared the latest updates on the neurological condition that affects over 65 million people worldwide, including 3.4 million in the United States, in a virtual epilepsy symposium hosted Nov. 6 by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS).

The Third Annual Epilepsy Symposium consisted of segments focused on pediatric neurology and neurosurgery, Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP), and seizures and epilepsy in older adults, as well as a neuropsychology update. A question and answer session followed in which the experts answered frequently asked questions as well as specific questions from audience members.

The symposium was aimed at patients, family members, caregivers and health care providers.

Harshad Ladha, M.D., an assistant professor of neurology who joined UAMS in August, used a series of colorful slides to show how seizures occur like “an electrical storm” in the human brain, which has about 86 billion neurons that communicate by electrical impulses.

He said that under a new definition of epilepsy, about one in 10 people will have a seizure and about one in 26 people will develop epilepsy in their lifetime. In older adults, he said, symptoms that constitute epilepsy can often look like something else to doctors unfamiliar with the disease, which is why it’s important to obtain a detailed history of the patient and conduct relevant testing.

For people 50 and older, “epilepsy is the third most common neurological disorder after stroke and dementia,” Ladha said.

“Not everyone who has a seizure has epilepsy,” Ladha said, explaining that other causes of seizures in the older population include stroke; neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s dementia; brain tumors; a central nervous system infection; a traumatic brain injury; metabolic disorders such as low blood glucose or low sodium; and alcohol or substance withdrawal.

In about half of older adults, he said, “we don’t know why they have seizures.”

Ladha said that some other common conditions in older adults that shouldn’t be confused with epilepsy are syncope, a loss of consciousness due to low blood pressure; delirium caused by electrolyte imbalances; transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) caused by a temporary blockage of a blood vessel in the brain; transient global amnesia (TGA); psychogenic and behavioral spells; and sleep disorders, including acting out dreams or sleep walking.

He said that for two out of three adults, symptoms are controlled by medication alone, and that newer medicines for epilepsy have a lesser chance of causing side effects than older drugs. Besides medication, other treatment options are surgery and the implantation of a neuromodulation device.

Gregory Albert, M.D., MPH, a professor of neurosurgery at UAMS and chief of pediatric neurosurgery at Arkansas Children’s, discussed the latest methods of treating epileptic patients, such as responsive neurostimulation, an invasive or noninvasive means of purposely modulating the nervous system’s activity.

Albert said a neurostimulator can sense a seizure and try to disrupt it before it occurs, and can take snapshots of brain activity throughout the day.

“It’s a very intricate device, quite ingenious, and works quite well,” he said. “About 69 percent of patients respond to it, and on average, there is about a two-thirds reduction of seizures.”

The device was FDA-approved in 2014 for patients 18 and older with partial onset seizures, and has been used in some younger patients as well, Albert said.

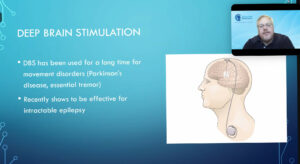

He also discussed deep-brain stimulation, which has long been used to control movement disorders, noting that it has recently proven to be effective for treating intractable epilepsy, in which seizures fail to be controlled by medication. About one third of epilepsy patients will develop intractable epilepsy, he said.

Salman Zahoor, M.D., a UAMS assistant professor of neurology, said one of the most common complications of epilepsy is depression — an association that has been known for some time and may be due to shared structures of the brain. He said doctors should always use the appropriate form of treatment for depression and know that some anti-seizure medications can worsen some depressive symptoms by affecting neurotransmitters in the brain.

“Some seizure medicines may also affect cognitive and memory functions,” Zahoor said.

He also discussed Sudden Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP), which is a leading cause of death in patients with epilepsy, particularly in people with more frequent seizures. Among the risk factors he identified for SUDEP, based on research studies, are experiencing frequent or recurrent seizures, the onset of epilepsy before age 15, having three or more convulsive seizures a year and poor adherence to a medication regimen.

Other presenters were Kapil Arya, M.D., an associate professor of pediatrics and director of the Associated Neurology Program; Adrianne M. Parkey, M.D., an assistant professor and pediatric neurology specialist; and Jennifer Gess, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and a clinical neuropsychologist.