Dream Land Discussion: How West Ninth Street Shaped Little Rock

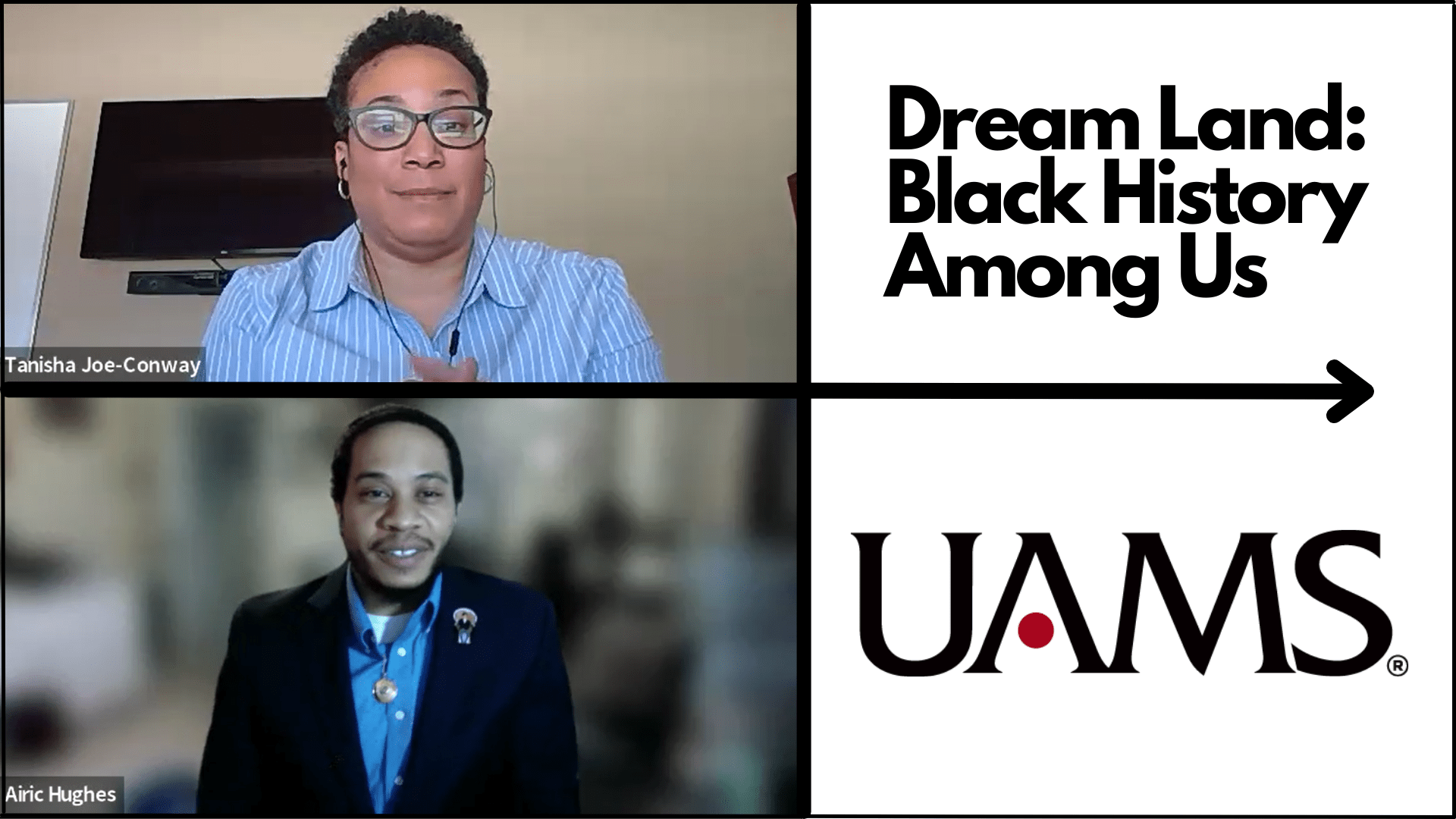

| March 25, 2022 | The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Division for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion hosted a virtual event to discuss Dream Land, a documentary about Little Rock’s West Ninth Street and how urban renewal shaped the Black community.

The documentary, produced by Arkansas PBS, sheds light on how an area of Little Rock became the center of the Black business district and was promptly shut down after the Federal Housing Act of 1949 was passed.

After the civil war, many freed slaves settled in the area and it became “a city within a city.” By the 1940s, the Dreamland Ballroom within Taborian Temple was used for many dances and social gatherings. It became known for high-profile events with musicians like Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, B.B. King and others performing there.

Not only was the entertainment industry prospering, but the area had pharmacies, hospitals and grocery stores – anything residents might need. Businesses thrived, creating a strong local economy.

During World War II, Black soldiers frequented the area, creating a business boom. The music, pool halls and nightclubs also attracted high school and college students as well as aristocrats. However, the urban renewal efforts led by the Federal Housing Act of 1949, which aimed to modernize “blighted” areas, brought the flourishing neighborhood and businesses to a halt.

Although it was promoted as a way to beautify cities and get rid of old, dilapidated homes and buildings, many community members felt the federal policy was actually used to racially redistrict Little Rock. The West Ninth Street area was a successful, thriving community, yet it was targeted as part of the urban renewal push.

Sharanda Williams, assistant dean for student affairs and diversity at UAMS, and Odette Woods, senior director for staff diversity, equity and inclusion, served as facilitators for the panel discussion.

Panelist Airic Hughes, a Ph.D. in History candidate at the University of Arkansas and the founder of Visionairi Enterprises, said the fact that Black wealth existed in the area defied the ideology of the time.

“Black people are the only group of enslaved people who became citizens of the country they were enslaved by. Their success flipped social ideas on their head,” he said.

Panelist Tanisha Joe-Conway, a producer for Arkansas PBS, said they chose to call the documentary Dream Land because that’s what the West Ninth Street community was.

“It was where members of the community could be free. They could walk on the street or go into businesses and see people who looked like them,” she said. “Look at what we were able to build. The ancestors of slaves built grocery stores, hotels, salons and hospitals. They had all these things right there.”

In the late 1800s and well into the 1900s, segregation became legal through the implementation of Jim Crow laws. In Arkansas, Blacks and whites could not share railroad coaches, streetcars or bathrooms. They could not gamble together, vote together, live together or get married.

“The statutes were in place to tell Black people what they could and could not do,” Joe-Conway said.

“Jim Crow became code for larger anti-Black policies,” Hughes said.

The civil rights movement picked up steam in the 1950s, and by 1954, public schools were required to be integrated. Central High School was famously desegregated after nine students were able to enroll following a tense stand-off staged by then-Gov. Orval Faubus who mobilized the Arkansas National Guard to prevent any Black students from entering the school. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

And yet, social separation was ramping up with the urban renewal policies.

“Central High School desegregated while the rest of the community became more segregated. It was resegregation following desegregation,” Hughes said.

Black business owners were forced to sell their properties or face eviction. Housing projects on the edge of the city were built for the displaced Black community members, away from white neighborhoods. More and more private schools popped up around Little Rock, hindering integration.

“Many decisions were made without community members at the table,” Joe-Conway said.

Along with urban renewal, construction of the I-630 further separated Black people from the community, creating a visible racial and economic divide.

“There was a lack of diverse presence in decision-making spaces, leading to policies that shaped our lived experience,” Hughes said.

Telling the story of the past, including the uncomfortable truths, is key to progress, Joe-Conway said.

Today, the only remaining structure from the neighborhood’s heyday is Taborian Hall, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

The panelists and facilitators agreed that the West Ninth Street area should be commemorated, whether by placing historic markers along the street or by rebuilding it altogether.

“Black history is American history. Rebuilding Ninth Street would celebrate Black culture and history,” Hughes said. “Dream Land is progress. Having this conversation is progress. Looking back will help us move forward.”

Dream Land can be viewed on AETN and on the Arkansas PBS YouTube page.