View Larger Image

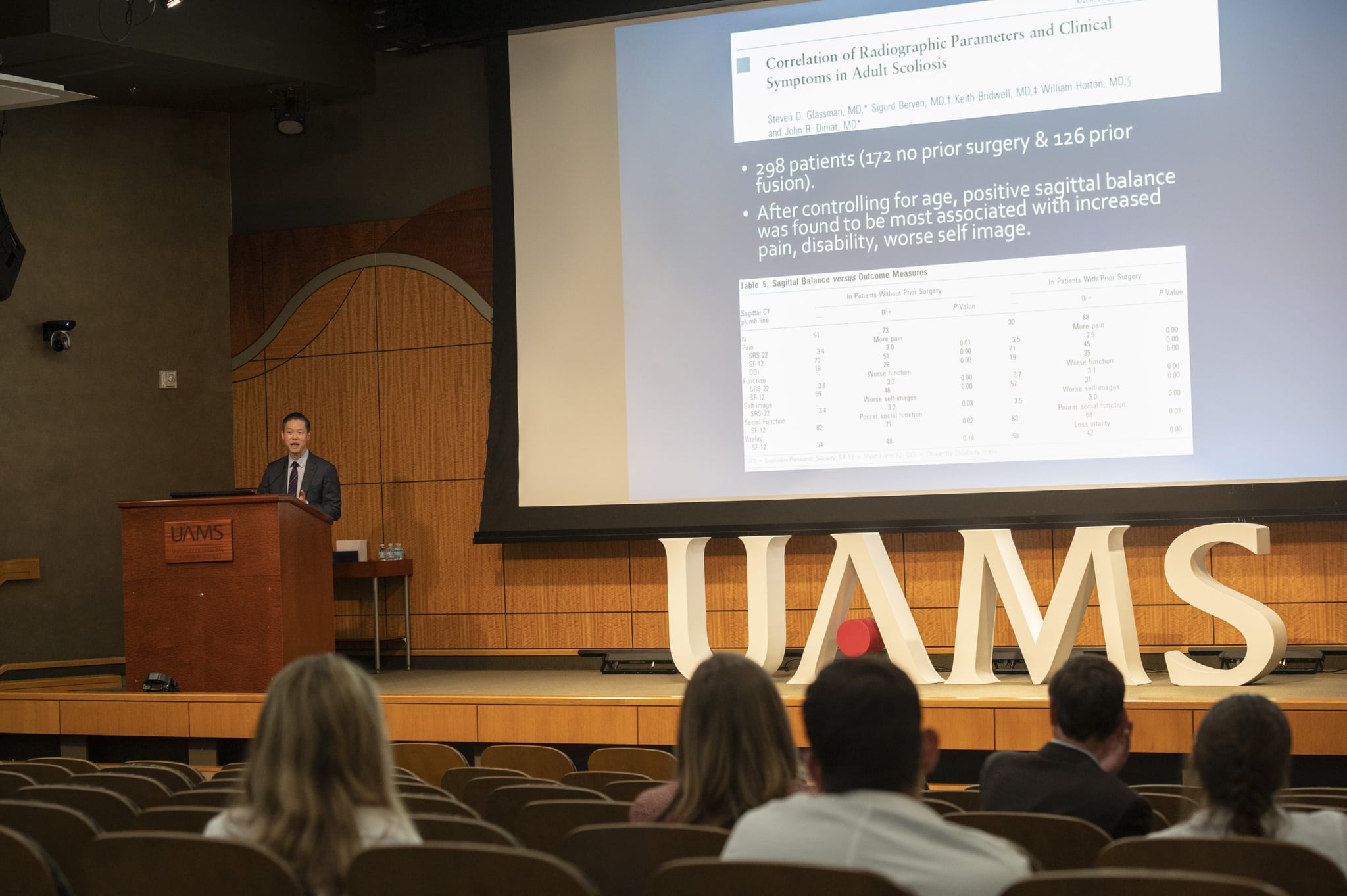

Paul Park, M.D., discusses spinal surgery during the annual Flanigan-Boop Lectureship in the Jackson T. Stephens Spine Institute.

Image by Evan Lewis

Memphis Neurosurgeon Says Surgery Isn’t Always Best Option in Treating Spinal Deformities

| | The surgical treatment of spinal deformities such as scoliosis was the subject of a Nov.4 lecture presented as part of the annual Flanigan-Boop Endowed Lectureship in Spinal Neurosurgery at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS).

Paul Park, M.D., a Memphis neurosurgeon, addressed a live and virtual audience of primarily physicians during his presentation in the Fred Smith Auditorium in the UAMS Jackson T. Stephens Spine Institute.

The lectureship, which was put on hold for two years due to the pandemic, honors the legacies of Stevenson Flanigan, a former chairman of the UAMS Department of Neurosurgery, and Warren C. Boop Jr., M.D., who together built the UAMS neurosurgery residency program.

Park, a spine surgery specialist who focuses on minimally invasive techniques, complex spinal reconstruction, spinal tumors and degenerative conditions, discussed the evolving role of specialized measurements on imaging tests in determining the need for and extent of surgical treatment.

A professor of neurosurgery at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center who practices at Semmes-Murphy Clinic and has published more than 250 peer-reviewed articles, Park emphasized that there is a close interplay between the lumbar spine and the pelvis.

He said that that despite evolving approaches to treating spinal deformities, it comes down to ensuring that a patient’s head is aligned over the feet, which is the definition of a normal center of gravity. Otherwise, the patient is expending energy and using accessory muscles just to remain in an upright posture.

Lecturer Paul Park, M.D., is presented with an Arkansas Traveler certificate by UAMS neurosurgeons Noojan Kazemi, M.D., left, and T. Glenn Pait, M.D., after the lecture.Evan Lewis

In discussing clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis patients, he said that although sagittal vertical axis is often used in correlating radiographic parameters, “SVA doesn’t actually assess any pelvic misalignment.”

Park also discussed “how our understanding of sagittal alignment has changed.”

He said the identification of different spine types has given rise to questions about which model or standard to use when considering how to correct deformities. Meanwhile, he said, it’s important to consider that a person’s pelvic alignment changes with age and varies with gender, and that it is becoming increasingly clear that radiographic parameters probably need to be modified.

Illustrating his points with charts and statistics, Park said radiographic numbers shouldn’t be given too much weight in surgical decision-making. Instead, “We need to actually look at the patient’s” individual factors, such as comorbidities like osteoporosis, obesity, diabetes and cardiac disease.”

“You can’t just use a classification system,” he emphasized.

In other words, sometimes less is more in deformity surgery.

He described times when it is best to “under-correct” a patient by primarily addressing pain relief and letting the patient’s body compensate for the deformity.

One of his patients, an 80-year-old man, “was treated just for his sacroiliac pain” and not for his spinal deformity, and “did well,” Park said.

In another patient, he said, “I didn’t correct her fully, but I got her to where” her head was again positioned over her feet, and a year later, she continues to do well.

“Sometimes it’s hard to say ‘No, I’m not operating on her,’’ he said, recalling his refusal to perform spinal deformity surgery on a petite, frail 80-year-old woman. “But sometimes, ‘no’ is okay. I don’t want a massive complication.”

For another female patient, he said, “I didn’t help her curve at all, but I helped her leg pain.”

“You need to see the patient and talk to the patient,” Park said. “Sometimes, it’s a small operation. Sometimes, it’s no operation at all.”

Park said that when the goal is to return the patient to the activities of daily living, minimally invasive and shorter surgeries are often the best option.