“Empire of Pain” Author Draws Large Crowd to UAMS for Lecture

| The 335-seat Fred W. Smith Auditorium was bursting at the seams April 26 as physicians, pain management experts and members of the community gathered to hear author Patrick Radden Keefe recount his investigative reporting into the origins of the opioid crisis in America.

A livestream of the presentation attracted nearly 100 viewers from such states as New York, Georgia, North Carolina, Minnesota, Illinois, Kansas, Washington, California, Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas as well as from Sweden, Mexico, France and Uruguay.

Author of the New York Times bestseller “Empire of Pain,” which examines the role that a prominent philanthropic family played in the crisis, Keefe said he stumbled onto the family’s hidden connections to the drug industry about a decade ago. At the time, he was writing articles for The New Yorker magazine about the business side of Mexican drug cartels and their various “product lines,” and noticed that the cartels had suddenly begun shipping more heroin to the United States.

He soon learned that the influx of heroin was related to an increasing number of Americans developing an addiction to FDA-approved, doctor-prescribed painkillers, which eventually led them to seek out heroin, a cheaper chemical cousin to the opioids, on the black market.

The history of the opioid crisis “is now three decades old, and it’s incredibly complicated,” Keefe said. He noted that while in 2010 the focus was on heroin, it has now shifted to fentanyl, which killed roughly 100,000 people last year.

Keefe said that the more he looked into the origins of the crisis, the more he became confident that it began “with one company and one drug. The company was Purdue Pharma, and the drug was Oxycontin, which was released in 1996.”

Before Oxycontin, he said, doctors routinely reserved opioids for only the most severe kinds of pain, in an effort to balance therapeutic benefits against habit-forming side effects. Then Purdue Pharma introduced Oxycontin as a nonaddictive alternative, even though the claim turned out to be false.

Keefe said he learned that Purdue Pharma was a privately held company of the Sackler family of New York. Having grown up in Boston, he said, he vaguely recalled the name from his visits to the Sackler Museum at Harvard University and later, after he moved to New York, the Sackler wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But he knew nothing about the family.

“Once you start looking for it, you see this name Sackler all over the place, always at these elite institutions, fancy universities, medical research facilities and art museums all over the world,” Keefe said. “And this was really interesting to me. I looked into it, and I learned that the Sacklers were this prominent philanthropic dynasty who were known chiefly for their generosity, that they gave lots and lots of money away — always with the stipulation that the Sackler name go on the wall.”

Keefe said he knew the family still owned Purdue Pharma, yet he couldn’t find a single mention of them on the company’s website.

“It feels like it’s not an accident that the family name is so prominent in one context and then, bizarrely, totally missing in another,” he said.

Intrigued, Keefe said, he began looking deeper at the family, first for a 2017 article in The New Yorker, where he is a staff writer, and then for the book, “Empire of Pain,” which he initially considered “a sort of family dynasty story about three generations of this family.”

He learned that immigrants Isaac and Sophie Sackler made their home in the Brooklyn borough of New York City after arriving from Europe in the early 1900s. Though they started out poor, he said, they formed a plan to build a family dynasty that included all three of their sons attending medical school and becoming doctors, which came to fruition.

Keefe said the oldest of the three brothers, Arthur Sackler, was a practicing psychiatrist, but his true love was medical advertising.

As the days of Big Pharma dawned, Keefe said, Sackler joined and then soon bought a boutique advertising firm. Then, Keefe said, Sackler began “importing into the world of drug advertising all of the pizzazz and the sexiness that was associated with selling cars or cigarettes at that time.”

“He’s both a brilliant physician, and he appears to be this very upstanding guy, but he’s also got a great sense for graphics,” Keefe said. “And his real intuition is that the way in which you sell drugs isn’t by thinking too much about the consumer but thinking about the doctor. The person you really want to seduce is the doctor. One of his contemporaries said that when it came to medical advertising, Arthur Sackler invented the wheel.”

Sackler’s first big success was in marketing Valium, Keefe said, but “not all of Arthur’s methods were what you would think of as necessarily kosher.”

For example, Keefe said, Sackler promoted an antibiotic in medical journals by claiming its endorsement by several physicians whose business cards were displayed in the ads. Then a reporter who tried to contact those doctors discovered they didn’t exist.

As Sackler became very wealthy, he started giving money to elite institutions that agreed to prominently display his family’s name in return, Keefe said.

Curious about what motivated Sackler, who rarely gave interviews, Keefe acted on a hunch that Sackler may have spoken to a student newspaper at Tufts University, where a building bore the Sackler name early on. This was before the Internet age, so Keefe had an archivist search through microfilm at Tufts to unearth just such an article.

In it, Sackler said that after his father, Isaac Sackler, lost all his money during the Depression, he told his sons they would have to finance their own paths to medical school, and emphasized to them, “If you lose a fortune, you can always go out and earn another fortune. But if you lose your good name, you can never get it back.”

Keefe said the sons embraced that philosophy after their father’s death by donating money to prestigious institutions, and by the time Arthur Sackler died in 1987, he was a well-respected celebrity of sorts.

Meanwhile, his brothers continued operating Purdue Pharma.

Keefe said that when he examined internal documents memorializing the company’s marketing meetings, he found discussions about plans to create an opioid derivative related to MS-Contin, a Purdue product more commonly known as morphine. But unlike morphine, the marketers wanted the new drug to be one that could be marketed more broadly than morphine.

After introducing OxyContin, which the company knew was more powerful than morphine, it intentionally avoided contradicting many physicians’ belief that it was actually milder, Keefe said.

Instead, Purdue “launched the biggest marketing blitz in the history of the pharmaceutical industry, very much in keeping with the model devised by Arthur Sackler.”

Soon, OxyContin became widely prescribed, and reports of its pain-relieving qualities soared. But after just a couple of years, complaints started coming in about “the magnitude of the devastation that’s coming from the drug,” Keefe said, forcing Purdue to acknowledge its addictive qualities — but only by blaming the “weak moral character” of the people who became addicted.

Then in 2007, federal prosecutors in the Western District of Virginia pursued a criminal indictment against Purdue Pharma. Eventually, the company was fined $600 million while its executives, who took the fall for the owners, avoided prison time.

Following “a tsunami of lawsuits” against Purdue Pharma, he said, “the story ends in a bankruptcy court in White Plains, New York.”

While the legality of the bankruptcy settlement is still pending before the U.S. Supreme Court, the company agreed in 2020 to pay up to $6 billion over 19 years to help remediate the opioid crisis, in return for immunity from the lawsuits.

Keefe said he learned that over several years, the Sackler family had moved much of

Purdue’s profits into private, offshore accounts, which allowed the family to retain its wealth despite the settlement. In fact, Keefe said, he calculated that the family could make payments strictly from the interest it continues to earn, without touching the principal.

He said the Sackler name has since been removed from some of the elite institutions to whom the family donated, largely because of the actions of a well-known photographer, Nan Goldin, who overcame an addiction to OxyContin and then sought to expose the family.

Keefe’s lecture, “The Secret History of the Sackler Family and OxyContin,” was part of the annual History of Medicine and Science lecture series organized by the UAMS Department of Neurosurgery and the Jackson T. Stephens Spine and Neurosciences Institute.

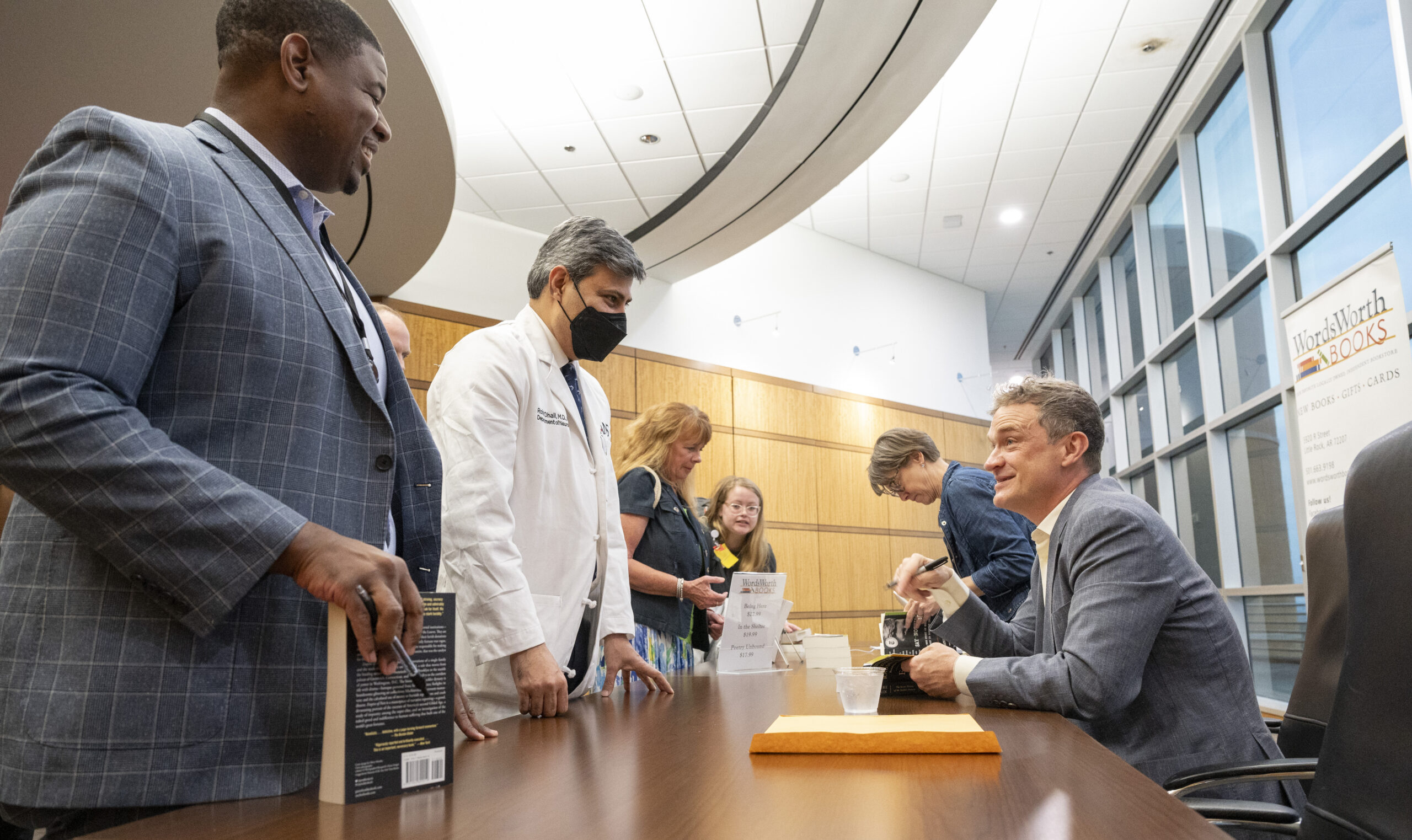

T. Glenn Pait, M.D., a neurosurgeon who is interim chair of the UAMS Department of Neurosurgery, talks with Keefe after the lecture.Evan Lewis

“Patrick Keefe was not only informative, but captivating, providing valuable insights into the opioid and OxyContin epidemic,” said T. Glenn Pait, M.D., interim chair of the department. “His ability to engage the audience was truly commendable. His lecture sparked thought-provoking discussions and left a lasting impact on some of the attendees.”

Pait said more than 300 people registered to watch the lecture in person and virtually, adding, “We have received overwhelmingly positive feedback. It was indeed one of the best lectures presented recently at UAMS.”

Afterwards, Keefe spent about an hour and a half autographing copies of “The Empire of Pain” and talking with audience members.