‘I’m Still Here’: Sickle Cell Patient Lives on Her Own Terms

| Susan Johnson, 62, of North Little Rock, has fought sickle cell disease her entire life. She was first diagnosed decades ago, before early screenings were common and when care was still evolving. So to make it to this point in her life as a sickle cell patient, Johnson said, is remarkable.

“My brother didn’t see his 24th birthday, and I’m four years older than he is,” Johnson said. “So I was already in what I understood to be borrowed time. I did not expect to be 32 years of age, and the fact that I’ve lived almost double is something that no one saw coming.”

Johnson was born with sickle cell anemia, sometimes called SS sickle cell because of the two “S” sickle cell genes inherited from each parent. Unlike other forms of sickle cell, hers is the most severe form of the disease and often results in multiple pain crises monthly.

Her brother Primus, who also had sickle cell disease, died at 23. The estimated life expectancy of sickle cell patients is more than 20 years shorter than average, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Johnson has spent her life learning about how her body responds to treatment for the disease. Her determination to speak up for what she needs has helped see her through. Don’t mistake it for fearlessness, though — she’s quick to correct that assumption.

“It’s not so much about being fearless as being able to advocate for yourself,” she said.

‘You Learned What Your Limitations Were’

Johnson was born in Indiana but spent most of her life in California’s San Francisco Bay area. Growing up with sickle cell was difficult for her family, with one or both children experiencing weekly pain crises, sometimes resulting in hospitalizations. It became a not so much a matter of limitation, she said, but knowing what the consequences were.

“Over the years you learned what your limitations were — what you could and could not do,” she said. “Many weekends were spent in crisis. Everyone else is getting ready for their weekend, and my brother or I, or both of us, would go into crisis at sunset and not be ready to interact with anybody until Monday, when we would be just well enough to return to school.”

Doctors wanted to restrict what Johnson could do, but her mother wanted her and her brother to have as normal of a life as possible. Johnson credits her primary care doctor, James P. Lockhart, M.D., along with other members of her family as well as her mother, with helping avoid repeated visits to the hospital or emergency room.

“There were not any guidelines, so she was making it up as she went along,” Johnson said. “A lot of what I went through was trial and error, and my mother had to be my champion in order to create the boundaries by which she would allow me to be seen.”

Enforcing those boundaries became increasingly necessary as Johnson grew older.

‘I Was the Unicorn in the Room’

In the 1960s, Johnson said she and her brother were diagnosed with sickle cell disease. At that time, sickle cell disease was still largely unknown. Blood transfusions and pain management were the only forms of treatment, and newborn screenings for the disease were more than a decade away. This led, Johnson said, to her being seen as a medical curiosity — and having to fight for her rights as a patient.

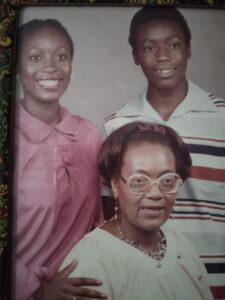

A younger Johnson, top left, with her brother Primus Jackson Johnson IV and mother Nadine Abel Johnson.

“Being the first diagnosed patient at my medical facility, there was a lot of interest in my case, as you can imagine,” Johnson said. “There were a lot of challenges that came with that, because when I was in the hospital, they really just wanted access to my blood. They would try to get it from me in every way possible for whatever reason possible.”

Her mother was by her side most of the time and helped keep curious eyes away. However, when she was alone, Johnson said the blood draws continued — sometimes in the middle of the night, taken from areas of her body that were not immediately obvious.

“They didn’t have to give the child a reason,” Johnson said. “But what they didn’t know about me is, I was not just the average kid. The minute my mom or some adult showed up that I trusted, I would tell them what they had done. There were a lot of battles going on between my mother and the hospital, for what they said was required and what she would allow them to do.”

Johnson said she was coveted for the possibility of advancing research and not treated like a person who mattered. In her experience, she said, too many medical professionals prioritized research over care.

“Unfortunately, treatment was not always at the forefront of individuals’ minds when my name came up on the chart,” she said. “I was the unicorn in the room, and they just wanted access to the unicorn so that they could have their experience with this disease — and the person, me, was too far down the list. It was not an easy experience. It was always challenging.”

Johnson is still wary of hospital stays today.

“It was absolutely a terrifying experience every time,” she said. “It wasn’t as if you would step into the hospital and the wall of protection was there — it was always a battle. The experience of it has made me a warhorse of sorts, in that I go into the hospital with my armor on. Even though I need treatment, I know that I might need to fight my way through it in order to get it.”

Moving to Arkansas and ‘Divine Timing’

Johnson moved to North Little Rock in early 2018, looking for a fresh start. Now, six years later, she still has challenges adapting to the weather. Weather conditions can trigger complications for sickle cell patients, and Johnson was no exception.

“It wreaked havoc on my body, big time,” she said. “A lot of the issues that were triggered during my arrival were based on my body’s inability to acclimate. I started wearing a mask before COVID. Whenever I go out, I wear a mask.”

Johnson managed to avoid hospitalization initially but later in 2018 came to UAMS via the Emergency Department for what would be a nine-day hospital stay. A second nine-day stay followed in the fall. At that point, she was introduced to the UAMS Adult Sickle Cell Program, which she visits occasionally for checkups.

“I’ve been able to, praise God, manage my sickle cell crises since September 2018 in-house as opposed to being seen by professionals, which was a goal,” Johnson said. “That was a goal of my medical team in California and my family’s personal goal, just because it was always such a difficult time to be in the hospital.”

Due to her personal and religious beliefs, Johnson does not accept blood transfusions. Instead, she manages her disease with a medication called epoetin alfa, which is normally prescribed to treat anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease, cancer chemotherapy or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Epoetin injections contain synthetic erythropoietin, or EPO, which helps the bone marrow produce more red blood cells.

For reasons she hasn’t been able to understand, Johnson said her body stops producing blood at a certain point, and the epoetin injections help her manage that. She learned about the drug while still in California, after a conversation with members of her Jehovah’s Witness congregation.

“The timing of everything, in my belief, was divine,” Johnson said.

Johnson said the “spiritual foundation” she has built over the years has helped keep her alive. It is the main focus of her life and has brought with it friends, community and hope.

“I give all credit to my higher authority, because it’s all been about a journey, and one I was propelled to be on because of my circumstances,” she said.

Johnson said she’s usually reluctant to share her diagnosis with others, but talking with other members of her faith has made her more introspective. She’s been told she should write a book about her experiences. Even if she doesn’t write one, Johnson knows her life has purpose.

“I understand that my being here is for a reason that I don’t necessarily have all the answers to,” she said. “My spiritual beliefs give me a hope that I wouldn’t have otherwise. My brother didn’t see his 24th birthday, so it’s very profound to me that I’m still here.”

Johnson remains hopeful that sickle cell disease will be better understood in time. For now, she’s glad to share her story and help future care take shape.

“Sickle cell disease has been a mystery throughout my life,” she said. “So much remains unknown. Shining light on the dark is something I’m honored to be a part of.”