Researchers Simulate Poverty to Understand Effects on Health

| It’s not necessarily a stretch to suggest that the ZIP code of a patient’s home address – or whether they have a home address at all – may offer as much insight into their health as measurements of height, weight, body temperature and blood pressure.

“It’s true. Research says that only about 20% of a patient’s health outcomes are related to treatment. The other 80% are related to other things, such as the economic, social and physical environments where they live, work and play,” said Leanne Lefler, Ph.D., APRN, an associate professor in the UAMS College of Nursing. “Poverty has more to do with health than treatment.”

For that reason, Lefler has partnered with Jennifer Stane, M.P.H., an instructor of dental hygiene in the UAMS College of Health Professions, on a project designed to teach students and faculty across campus how social circumstances can affect the health of patients and communities.

The project is of particular importance to Arkansas, she noted, as nearly 20% of Arkansans live in poverty, including one in four children and one in three among the disabled.

“Think about that,” said Lefler. “For every five patients we see each day, one of them will need extra support, statistically speaking. But right now we’re not so great at addressing that or even asking the right questions to address that.”

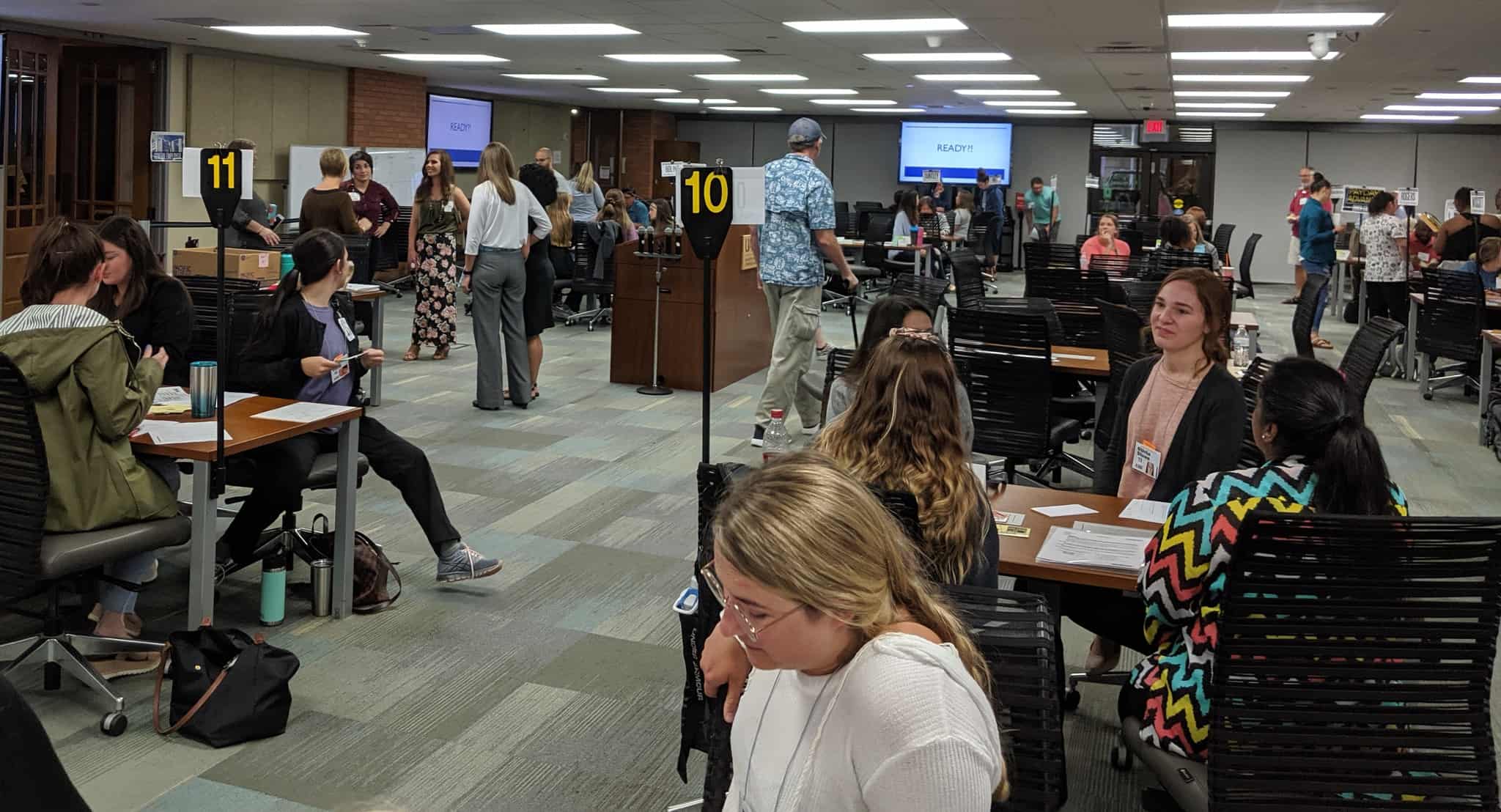

Volunteers ran stations simulating commercial, social and community services while participants managed their financial resources and dealt with life events.

To find the right questions, Lefler and Stane are co-leading a grant from the Office of Interprofessional Education that involves students participating in an intricate simulation in which participants, which can be students or faculty, undertake the role of a person living in poverty trying to balance financial demands of things like rent and groceries while also navigating social services and utilizing community programs.

Lefler purchased the simulation materials with grant funds from the Office of Education Development last year to incorporate into graduate nursing courses. At almost the same time, Stane, whose specialty is community dentistry, participated in training to administer the same simulation through a continuing education course held in Missouri.

After she returned from the training, Stane found out about Lefler’s purchase and contacted her to be involved in running the simulation at UAMS. They teamed up with Laura Smith-Olinde, Ph.D., of Education Development, and William Ventres, M.D., M.A., in the College of Medicine, to pursue a larger interprofessional education grant to conduct the simulation, which requires dozens of participants to run optimally, and invited students from throughout campus to explore how poverty effects health outcomes.

“In this exercise, participants face hard choices in a simulated environment,” said Lefler. “Some of them can’t afford groceries and have to get by on whatever is in the pantry. Some get evicted and became homeless.”

The pilot staging of the simulation, which involved 70 students and eight volunteers who played roles like social services workers and pawn shop owners, was held in late May. While data is still being analyzed, the results are expected to be instructive.

“Understanding poverty is relevant to pretty much any degree you can get on this campus,” said Stane. “At some point you’re going to run into a situation in which you’re dealing with somebody, whether from a client standpoint or a patient standpoint, who either is currently or has lived in a poverty-like situation.”

Living in poverty changes patient behaviors in ways that health care providers may not understand or might misinterpret, Stane said. For instance, a patient may skip appointments because they can’t afford the services or the time off to see a doctor. They might skip doses and stretch medications because they can’t afford prescription refills. Transportation may be a hindrance.

“There’s a lot that happens for patients between the moments they’re seeking care,” said Stane. “So we as providers need to think about what happens when they leave here. What happened just for them to be able to make an appointment?

“From a pharmacy standpoint, a medicine standpoint or a nursing standpoint, what we often write off as patient noncompliance really isn’t,” she continued. “It’s that they don’t have the resources to comply or are just trying to stay alive, keep a roof over their head and make sure they get their kids to school, keep them fed and keep the lights on.”

Lefler and Stane said that, while they understand the simulation can’t exactly replicate the lived experience of poverty, participants are instructed to take the situations seriously. When they do, , participants get a learning experience that goes beyond a logical understanding and extends to emotional learning. That will better equip health care providers to care for their patients.

“Evaluating the effectiveness will be an ongoing effort,” said Lefler. “But we think students who attend this simulation will demonstrate greater understanding of poverty and other social determinants of health. They’ll consider it in treatment decisions and collaborate with other health team members to address all of their patients’ needs in a patient- and family-centered care approach, which is what we advocate here at UAMS.”