Poison and Drug Information Center at UAMS Inspires Career Choices

| Spending a month last May in the Arkansas Poison and Drug Information Center helped Masha Yemets, a UAMS College of Pharmacy student, define the career path she wants to follow.

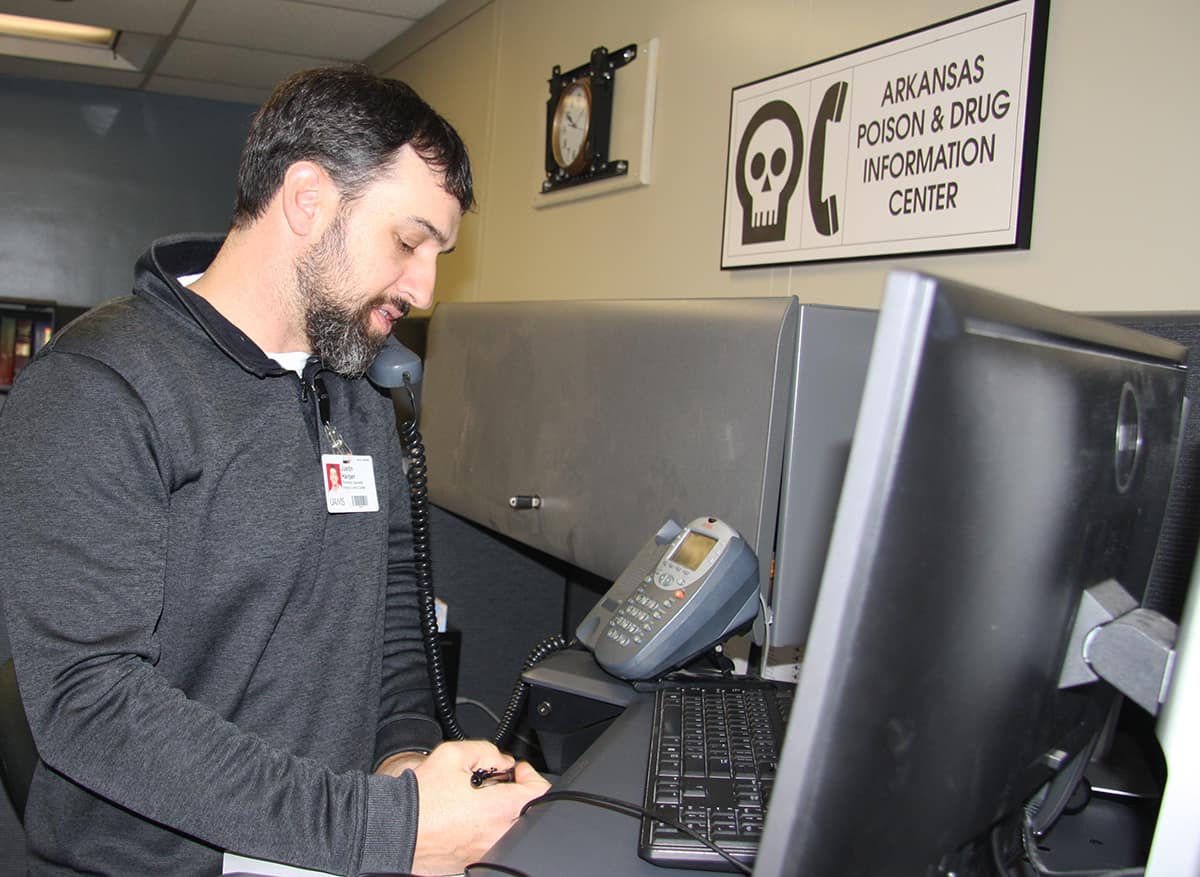

Yemets, who graduates in May, spent that month answering calls in the center from a broad cross-section of the public.

“I had an inkling I might enjoy toxicology, but the experience in the poison control center kind of sealed the deal for me,” Yemets said. “I wanted to see how the rotation went before I decided. It’s just so different than the typical pharmacy. It was so exciting dealing with different kinds of people and different phone calls and expanding my knowledge with each call.”

She would like to pursue becoming a clinical toxicologist when she graduates this spring.

Callers to the hotline can vary from a child who drank a cleaning fluid, an attempted suicide-by-overdose case in an Emergency Department, or a recreational drug user who consumed an unknown drug. These cases may have little in common except needing the center’s help.

Yemets said the callers are people of a variety of ages, cultural backgrounds and levels of knowledge. That diversity requires the pharmacist, nurse or other provider taking the call to constantly adjust and shift their approaches to be able to communicate the right information in way that is understood clearly enough to be helpful.

“You hone those communications skills to be able to relate pertinent information to so many different people. It could be talking to a patient or a physician,” said Courtney Gross, Pharm.D. “You have to be able to modify what you’re saying so they can understand it. Then, you can take that and apply it in your everyday life.”

Gross graduated in 2010 from the College of Pharmacy and took a job in the center during her fourth year as a student. Like Yemets, she loved it, and the challenges it presented to her.

“My passion for toxicology is what led me into Emergency Medicine as a specialty,” she said.

After several years working in emergency medicine in Minnesota, Gross now works as a clinical pharmacist for HCA Healthcare in Nashville, Tennessee, a job that still includes emergency medicine as one of her areas of specialty.

Gross also counts as mentors Howell Foster, Pharm.D., the center’s director and an associate professor in the College of Pharmacy, and Keith McCain, Pharm. D., associate professor in the college’s Department of Pharmacy Practice.

Although some state poison control centers are affiliated with colleges of pharmacy, the Arkansas Poison and Drug Information Center is one of only two poison control centers housed physically and organizationally in a college of pharmacy. The other is in New Mexico, Foster said.

The center was established in 1973. Although it receives state funding now, the College of Pharmacy for almost 20 years of its history was its sole financial support.

The strong connection the Arkansas center has to the College of Pharmacy positions it well to draw on the expertise of its faculty when confronting a new toxin or trend.

Foster said one of the biggest challenges facing the center is the variety of recreational drugs out there. It was relatively easy in the past to figure out what class of drugs a particular street drug might fall into, but now a new agent might not even test as its parent compound on a drug screen.

“With the emergence of so many synthetic drugs that can fall in the cannabinoid class, the amphetamine class or opioids class, it’s sometimes very challenging. With some of the drug classes, I cannot even name all the variants on all my fingers and toes,” Foster said. “The number of substances that people can get into is huge.”

Often, the symptoms of exposure are what help a specialist in the center determine what someone took, and fortunately, the established treatments for the majority are still effective, Foster said.

A national database helps the center staff answering calls to identify toxins and drugs along with treatments for exposure or misuse. Center staff also contribute case histories and information to the same database, sharing it nationwide. Once a call is completed, they upload it to the same database, typically within eight minutes, Foster said.

Cases are followed to a known outcome, which makes the pooled data extremely useful as it identifies trends and provides information to potentially modify treatment regimens.

He said about 75% of calls come from homes and 20-25% from Emergency Departments. About 65% of cases involve children 6 years old and younger who have “gotten into stuff” and about 13-14% are suicide cases. The remainder involve a mix of accidental exposures to a variety of chemicals.

Not every case is life threatening or one that will have a lasting, negative effect on a person’s health. In those cases, a center staff member doesn’t just provide information. They provide emotional support.

“The team environment from all the health care professionals is good,” Gross said. “Sometimes it’s just calming down folks and letting them know through tone of voice that it’s going to be OK.”