Sensory Room Lets Kids Work Through Problems

| A room once intended for isolating patients in distress has become a favorite of the UAMS Psychiatric Research Institute’s youngest charges, thanks to the addition of a number of components designed to both calm and stimulate them.

The Child Diagnostic Unit, an inpatient unit for patients 2 to 12 years old, was intended to be used for adult patients when the Psychiatric Research Institute opened in 2008. The unit’s seclusion room, designed for an agitated adult patient, was deemed unnecessary by the Child Diagnostic Unit’s staff, who began to look for alternative uses of the room.

“We wanted to use it as something other than a consequence or timeout,” said Diane Hanley, a registered and licensed occupational therapist who joined the staff in 2009. “We wanted to use it in a preventive way, as a tool to get them calm.”

Occupational therapy intern Olivia Brown sits with therapeutic stuffed animals designed to soothe young patients.

Hanley and the unit’s other registered and licensed occupational therapist, Pam Handloser began to look for items staff members could use to address some of their patients’ problems. Off and on for four years, they studied approaches to handling patients with disruptive behaviors.

“There’s no wrong way for a kid to act. We were looking for therapeutic interventions to put in the room to allow them to work through their problems,” said Handloser.

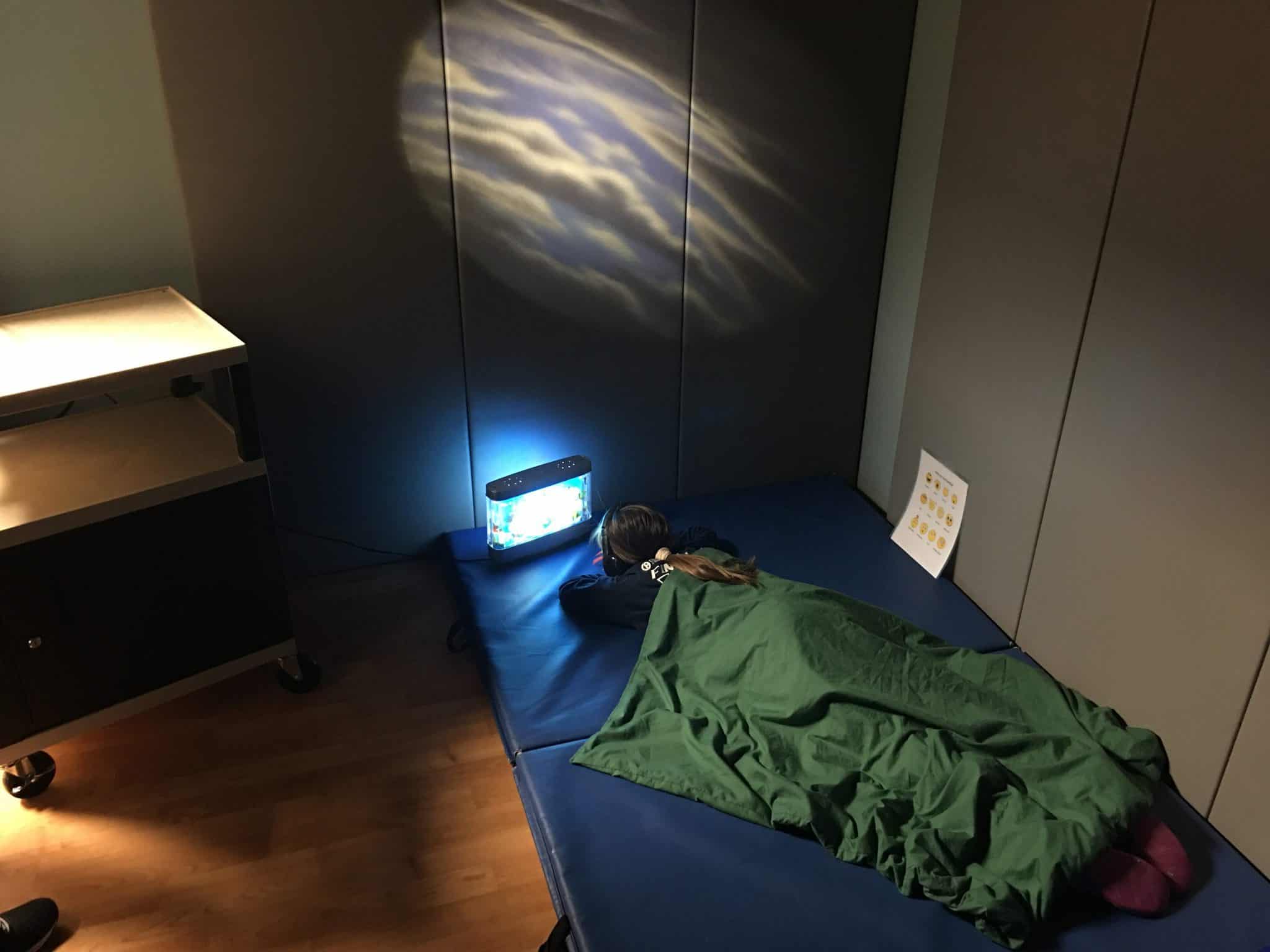

Handloser and Hanley, with help from a series of grants, incorporated noise-cancelling headphones, weighted blankets, soothing music, a yoga ball, a mini-trampoline and tumbling mats to create a comfortable environment for their patients.

“It’s goal oriented, you go in there for specific reasons, not for punishment,” said Hanley.

Michael (not his real name), 10, had a history of significant behavior problems before coming to the Psychiatric Research Institute. Diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, Michael had a history of aggression toward his parents, siblings and himself. His instability made it impossible for him to attend regular classes despite the fact that he had an average IQ.

Once he was admitted to the Child Diagnostic Unit, the staff noticed Michael was unable to communicate his needs and would routinely pace the unit, endlessly banging into walls and doors. His difficulty in communicating with others and his aggressive behavior made the staff believe he would benefit from time in their newly designated “sensory room.”

Regular visits to the sensory room and the use of massage techniques employed by the occupational therapists led to a decrease in Michael’s aggression and allowed him to relax around others. He was able to eventually identify feelings of boredom and difficulty in entertaining himself as the cause for his disruptive behavior. The staff used this information to provide him with activities structured to meet his needs, including games he could play on his own and instructional drawing books.

Michael’s father was on hand for one of his visits to the sensory room and worked with Handloser to learn more about some of the techniques used to ease his agitation.

“We gave the father some sensory integration handouts to take home along with some suggestions on how to modify his son’s environment at home and school to help him when he began to feel restless,” said Handloser.

Handloser and Hanley have worked extensively with the Child Diagnostic Unit’s staff to train them how to use the tools of the sensory room and how to recognize possible triggers for disruptive behavior.

“We expect to see this room reduce the need for additional medications, improve the patients’ skill development, increase their sleep time and open up a positive line of communication between the staff and the patient,” said Handloser.