View Larger Image

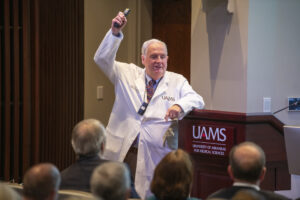

Kent Westbrook, M.D., entertains his audience while offering serious life lessons.

Image by Bryan Clifton

Kent Westbrook, M.D., Keeps Audience Laughing While Delivering Wisdom

| Laughter spilled out of the Walton Auditorium and three overflow rooms during much of the inaugural Last Lecture, delivered Nov. 16 in the Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute by Kent C. Westbrook M,D., distinguished professor of surgery.

A leader at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) for five decades who continues to see patients and train surgeons, Westbrook was nominated by colleagues to present the first talk in the planned annual series, “The Last Lecture: Lessons from a Lifetime of Learning.”

Organized by the UAMS Emeritus Society, the series pays tribute to a late-career or retired faculty member while sharing the honoree’s wisdom and insights — a tradition at many academic institutions.

In addition to the standing-room-only crowd in the auditorium and live feeds in three nearby rooms, the lecture was shared with a virtual audience.

“I can’t think of anyone in the history of UAMS more deserving to give the inaugural Last Lecture than Kent Westbrook,” said Richard F. Jacobs, M.D., chair of the society who retired in 2017 after 35 years at UAMS, including 11 years as chair of the Department of Pediatrics.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Westbrook worked with colleagues to develop comprehensive cancer programs at UAMS, eventually co-founding the Arkansas Cancer Research Center, the predecessor to the Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, and serving as its founding director for 14 years. He also directed the Division of Surgical Oncology in the College of Medicine for 11 years.

C. Lowry Barnes, M.D., a former student of Westbrook’s, describes the fear that Westbrook’s Sunday School invoked in students.Bryan Clifton

Two of his former students, C. Lowry Barnes, M.D., chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, and Ron Robertson, M.D., chair of the Department of Surgery, introduced him by remembering the indelible impression he made on them during “Sunday School.”

“Everybody who did any kind of surgical rotation knew about Sunday School here,” Barnes said. “Sunday School was the early morning meeting in the cafeteria when Dr. Westbrook got to ask questions, usually of the residents.”

“He asked all about the patient — their history, their labs — and all about their operation,” Robertson said. “It was pretty simple: If you didn’t know, you didn’t do.”

Sunday School caused a lot of anxiety among students who were subject to being called on and held accountable for what they didn’t know. No matter how much students tried to impress Westbrook, “he always knew more,” Robertson said.

Both veteran surgeons remembered how they struggled valiantly to earn Westbrook’s respect, seemingly to no avail. Barnes said Westbrook didn’t even seem to know his name — although years later, he learned that Westbrook had submitted an unsolicited letter of recommendation on his behalf.

“You know, I’ll even admit today, I’m a 63-year-old man and if I come around a corner and run into Dr. Westbrook, I get a little tachycardic, and I break into a little sweat,” Robertson said, generating laughter. “It’s like, what’s he going to ask me, and am I going to know it?”

On a more serious note, Robertson said, “He taught us many, many surgical lessons, but he also taught us life lessons.” Among them, he said, were always say yes, be pleasant and respectful with patients and other physicians, think of others ahead of yourself, always be thinking ahead, and if you don’t know where you’re going, there’s no way you can lead the team.

Westbrook earned his medical degree from UAMS in 1965 and then completed his general surgery residency before leaving for a surgical oncology fellowship at MD Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute in Houston. He returned to UAMS in 1972, and in the 51 years since, Robertson said, has influenced and trained at least 230 surgeons.

“I think I can speak for a lot of people here,” Robertson said. “We hear your voice in the back of our heads quite frequently when we’re having difficulties. You certainly had a huge impact on our education. You always pushed our boundaries, you always made us better and most of all, you always made us a better person at the end of it.”

Westbrook’s theme was Think Past Lunch, which he highlighted by several points, starting with “Don’t Be Stupid,” during which he revealed examples of things he did in his early medical career that he wouldn’t do now, such as displaying images from Playboy magazine at an Internal Medicine Grand Rounds on breast cancer.

He used photographs interspersed with cartoons, projected on a large screen, to make his points.

Westbrook’s wife, Jonnie, sits next to him while listening to his former students describe him.Bryan Clifton

In addition to sharing his personal history — which included attending the McKendree Church in Logan County, for which his grandparents donated land in 1883, as a young boy, and his Aug. 13, 1961, marriage to Jonnie Kay, the only woman he ever dated — he sprinkled in life lessons.

He said he and Jonnie Kay were married shortly before he started medical school at what later became UAMS, and everyone was required to live in the dormitory. He and his bride spent their honeymoon in the dorm, and their first daughter, September, even had a makeshift crib that consisted of a drawer in a built-in cabinet in the dorm room, he said.

The couple would have two more children, son Coleman and daughter Fara, by the time he finished his residency. Jonnie Westbrook and all three children listened from the auditorium.

Westbrook weaved humorous anecdotes throughout his lecture to illustrate life lessons that included “You Are Not as Important as You Think,” “You Are Important,” and “Finish Things Well.”

Richard Jacobs, M.D., chair of the UAMS Emeritus Society, introduces Westbrook’s lecture to a packed auditorium.Bryan Clifton

After describing a failed attempt to impress his young children by using his doctor skills to rescue an injured motorist, he became more serious, saying, “As a doctor, we are important to our patients and to society, and we should be important in volunteer organizations.”

“People think I was harsh at times,” he conceded, drawing chuckles. “The rule at that time basically was: see one, do one and teach one, and that’s because we didn’t have much faculty. When I came on the faculty here in surgery, we had three full-time faculty. Now we have nearly 50, and they can do almost as much work as the three of us.”

Westbrook said he learned over the years that it is important for people to have positive feedback.

“When we do the best we can, we make mistakes,” he said, revealing some of his that still haunt him. “We have to tolerate those mistakes and encourage people.”

Still, he said, “I’m convinced that we don’t stress people enough in the education system today, because a doctor is going to have stress at some point. At some point, they’re going to have to decide whether to do a tracheostomy, whether to put a chest tube in, whether to shock the patient, and they’re not going to be able to check with Dr. Google or the team or three groups of consultants. They are going to have to make a decision. So I think learning how to handle stress is important.”

“But,” he added, “you’ve got to be somewhere in between. Aristotle talked about the Golden Mean on Ethics: don’t be too good and don’t be too bad. Goldilocks is the same sort of thing. You want something that is not too hot and not too cold.”

Acknowledging his slightly wavering philosophy over the years on educating students, he said, “The training of students and residents needs to involve stress, but it also needs to involve support. I probably did not emphasize the support early on.”

A wave of laughter filled the room, and he added sheepishly, “I think after my daughter went through medical school, I might have been more supportive.”

Westbrook said that one of the best pieces of advice he received came from Doyne Williams, M.D., who was the chief resident during his residency.

“One of the first things he told me was think about what could happen in surgery that’s bad and know what you’re going to do when that happens. And that’s a critical thing.”

Westbrook said the Morbidity and Mortality conferences that the Department of Surgery holds weekly are “very important.”

“We talk about every patient who had a complication or died. In a very open, honest way, we try to analyze: ‘Why did this happen? Was it a mistake in diagnosis? Was it a mistake in treatment selection? Was it a technical mistake in the operating room? Did they not get adequate post-operative care?’

Westbrook gives a history lesson while displaying a photograph of the implosion of the dormitory where he lived as a student and young father.Bryan Clifton

“I think that approach is important in all of medicine,” he said, displaying on his screen the words: “Never stop learning, because life never stops teaching.”

He praised Sarah E. Harrington, M.D., director of the UAMS Division of Palliative Medicine, noting that “One of the things I’m very proud of is the development of our Palliative Care program.”

“I wrote a letter of recommendation for a promotion for her a couple of years ago,” he said, “and in that letter I said, ‘I want Dr. Harrington to be my doctor, but not today.’

Displaying a photograph of him and his family at the Gala for Life, an annual fundraiser for the Cancer Institute that they never missed, he said, “I think physicians should participate in the support of the College of Medicine, the medical sciences campus, the Cancer Institute, whatever they’re interested in.”

Winding up his talk, he said, “We need to learn how to finish things well.”

He recalled a very touching event while attending a medical school honors convocation in the 1990s. An African American woman approached him and said he had delivered her baby in 1965.

Westbrook said that back then, many young African American women delivered babies at UAMS without much anesthesia.

He said the woman motioned to one of the graduating seniors, saying, “This is the baby you delivered.”

“Now this is what UAMS is all about,” Westbrook told the audience. “We take care of people who can‘t get things for themselves. We give people the opportunity to be as good as they can be.”

Then, with Bob Dylan’s song “Forever Young” playing in the background, Westbrook added, “It’s easy to come in in the morning and say, ‘What have we got going on this morning, and then what are we going to do for lunch?’ It’s important to think past lunch. Have fun in what you’re doing, and then try to stay forever young.”

Video of the presentation is available here.