View Larger Image

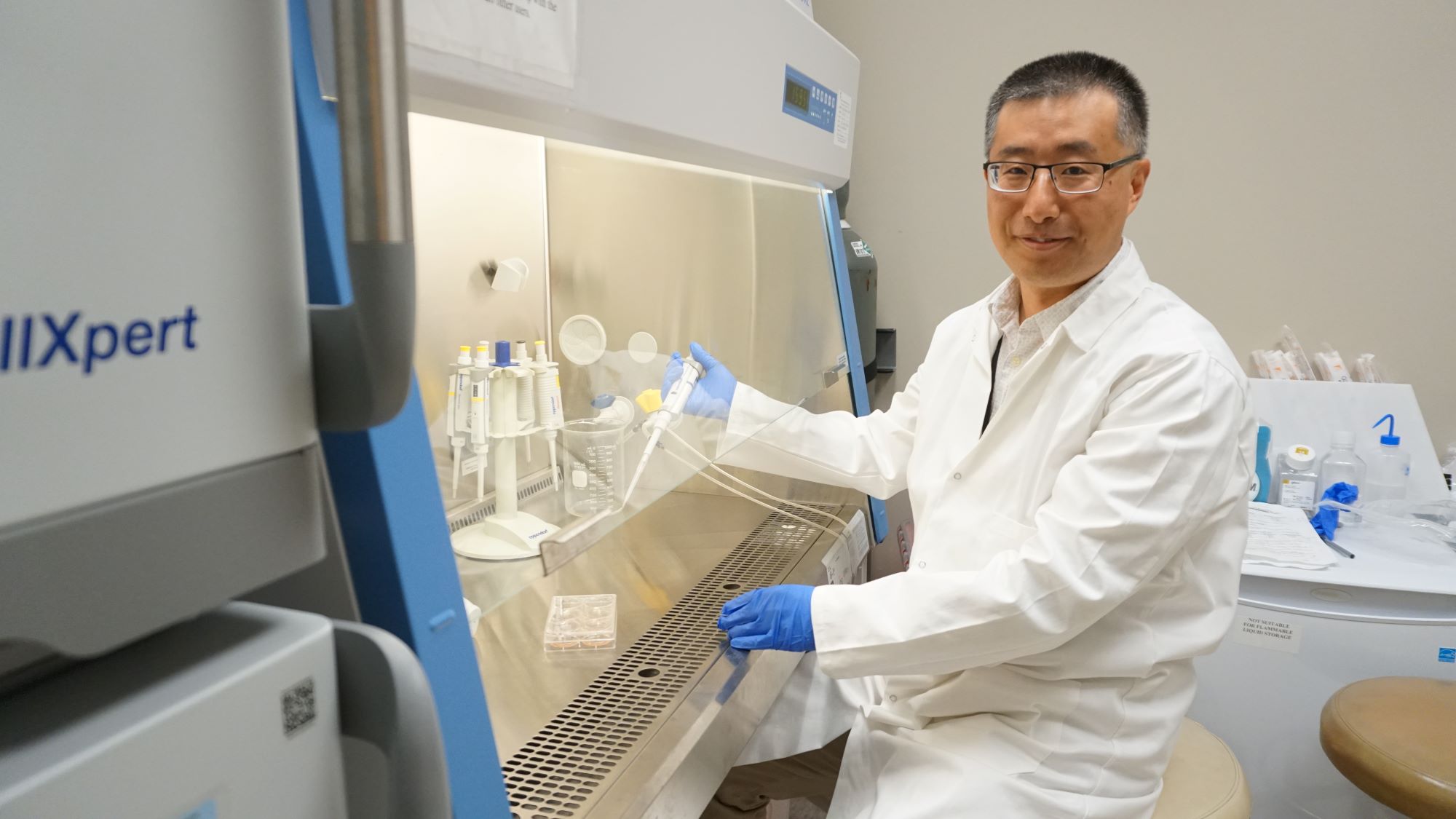

Huiliang Zhang, Ph.D., in his lab at UAMS.

UAMS Researcher Receives $1.8 Million NIH Grant to Study Key Cell Processes in Energy Production

| LITTLE ROCK — Huiliang Zhang, Ph.D., at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), will use a $1.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study proton leak, a process within the body that affects metabolism and energy.

Although scientists have been aware of proton leak for decades, Zhang said, little is known about its underlying causes, how prevalent it is across organ systems, and whether it has benefits or harms.

Proton leak is like a tiny leak in a cell’s energy system. There is a proton gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Energy is made when protons move a certain way across a cell’s mitochondrial inner membrane. However, there can be a small portion of protons crossing the mitochondrial inner membrane that are unable to produce energy. This is called proton leak.

Zhang is an assistant professor in the College of Medicine Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology. His research has previously focused on the heart, but the five-year award from the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) will allow him to broaden his scope. Using a new fluorescence test that he developed, Zhang will measure proton leak levels in the cells of different organs and determine the molecular mechanisms responsible for proton leak.

His findings will inform his next effort to find potential drug targets that can either increase or decrease the levels of proton leak.

For example, he said, chronic, excessive proton leak in the high energy-demanding heart muscle would make it weaker, which would call for a drug that could reduce proton leak.

“For some cases that mitochondria are not working efficiently, maybe we need some proton leak blockers to make proton leak less,” he said.

On the other hand, increasing proton leak in some tissues might be beneficial, for example, for someone trying to lose weight.

“When the proton leak is elevated, the mitochondria need to work much harder to produce energy, which increases metabolism,” he said. “This could be beneficial to someone struggling to lose weight.”