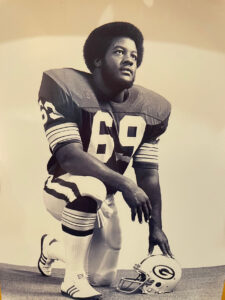

Former Razorback, Green Bay Packer Credits God and UAMS for Keeping Him Alive

| Nothing seems to slow Leotis Harris down or take the smile off his face.

As a teenager, he was a star football player at Hall High School in Little Rock. From there, he became the first Black All-American Arkansas Razorback football player. Then, after being drafted in 1978 into the National Football League, he spent six years as an offensive lineman for the Green Bay Packers.

It’s fair to say he is used to getting knocked around. But even when the hard knocks include a multitude of health problems over the years, he always gets back up and stays positive.

Now, nearly three years after undergoing a kidney transplant at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and nearly two years after undergoing the amputation of his right leg below the knee, the 68-year-old retiree doesn’t let the setbacks keep him from enjoying life.

“Being an ex-athlete, I love working out, going to the gym, working in the yard, planting flowers,” he said recently as he and his wife, Gloria, who will celebrate their 50th anniversary in September, sat in the lobby of the UAMS Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute. He had just received a monthly infusion to keep his immune system from rejecting the donated kidney.

“I’ve had a lot of issues with my health,” he said, recalling a kidney cancer diagnosis in 2001 that resulted in surgical removal of the cancerous organ, heart bypass surgery in 2006 due to a blockage, and struggles with diabetes and high blood pressure.

Before he received a deceased donor kidney in December 2021 in a transplant performed by UAMS surgeon Raj Patel, M.D., he spent four years on dialysis. The first year, the treatments created such a strain on his body that afterward, “I was so wiped out that I would have to come home and go straight to bed.”

The dialysis treatments were less strenuous during the next three years, however, after he was able to receive them from a smaller machine at his home. But there was still anxiety, because no one knew if a kidney would become available in time to save his life.

In 2018, a cousin started an online effort to find potential living kidney donors and to raise money for Harris’ share of the transplant costs, but “no one came to me and said they wanted to donate a kidney except for this one woman in Tennessee,” he said.

While grateful, Harris said, he was reluctant to accept the offer, assuming tests showed she was a match, because she was very young, and he didn’t want to put her through surgery.

As it turned out, he said, “We had a match before she could do anything. It was from a young person who died and whose organs were donated.”

Harris said his life improved dramatically after the transplant.

But a year later, an ongoing problem with his right foot worsened to the point that doctors wanted to amputate the leg below the knee to prevent any infection from spreading rapidly to other parts of his body.

“I wasn’t able to do anything,” he said. “It wasn’t mental. It was physical. I had a boot made so I could sort of get around, but I couldn’t do much. They wanted to amputate my leg, but I wasn’t ready. I had to come to grips with it. I had to have faith that everything was going to be OK.”

“I had Charcot foot,” he said, referring to a rare complication of diabetes-related nerve damage that causes reduced sensation in the feet and lower legs while the bones and joints become soft and deteriorate.

Finally, he told himself, “I know God has been watching over me for a long time, and I know I can’t do it myself. I just adopted a positive attitude.”

Looking back on his serious health problems, Harris said, “I think losing my leg was the hardest thing to get through.”

But a year and a half later, he breaks into a broad smile when asked how he has managed to stay so upbeat.

“It’s just having faith in God and believing,” he said, gesturing with his arms for emphasis. “God wants us to do our part, and God will do the rest. We just have to do the best we can, and he will step in and help us.”

Harris said he has adjusted well to a prosthesis that allows him to walk. His wife, Gloria, said he has good days and bad days, but overall maintains a positive attitude.

“I’m not mentally depressed because I had the amputation,” he said. “I feel great. I’m thankful just to be alive.”

He said part of his mindset comes from being an athlete.

“Being an athlete, you’ve got to do right in order to be right,” he said. “You’ve got to exercise, you’ve got to watch what you eat, you’ve got to avoid high cholesterol. It’s about being aware of what you’re doing and listening to your body. It tells you what’s going on. You just have to listen.”

On that note, his wife announced it was time to go get some breakfast and Harris agreed, rising to his feet with a big smile on his face.

It’s easy to see why the late Frank Broyles, Arkansas’ head football coach from 1958-1976 and athletic director from 1973-2006, once called Harris “a natural leader” who was respected by other players and inspired them to play better.

In more than 30 years since Harris returned to Arkansas from Wisconsin, worked at Tyson Foods and retired, he has continued to collect accolades for his athletic abilities. He was named to Arkansas’ All-Decade Team for the 1970s, then to its All-Century Team. In 2005, he was inducted into the UA Sports Hall of Honor, and in 2010, at age 54, he was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame.

Now, the man who was once dubbed “one of the greatest Razorbacks ever” by an assistant coach, Ken Turner, is a contender for the College Football Hall of Fame Class of 2024, which will be announced next year.

Meanwhile, Harris said he plans to keep enjoying life.

“You’ve got to do what you’ve got to do to make it through,” he said. “Sometimes you’re going to win, sometimes you’re going to lose, but you’ve got to stay positive.”