View Larger Image

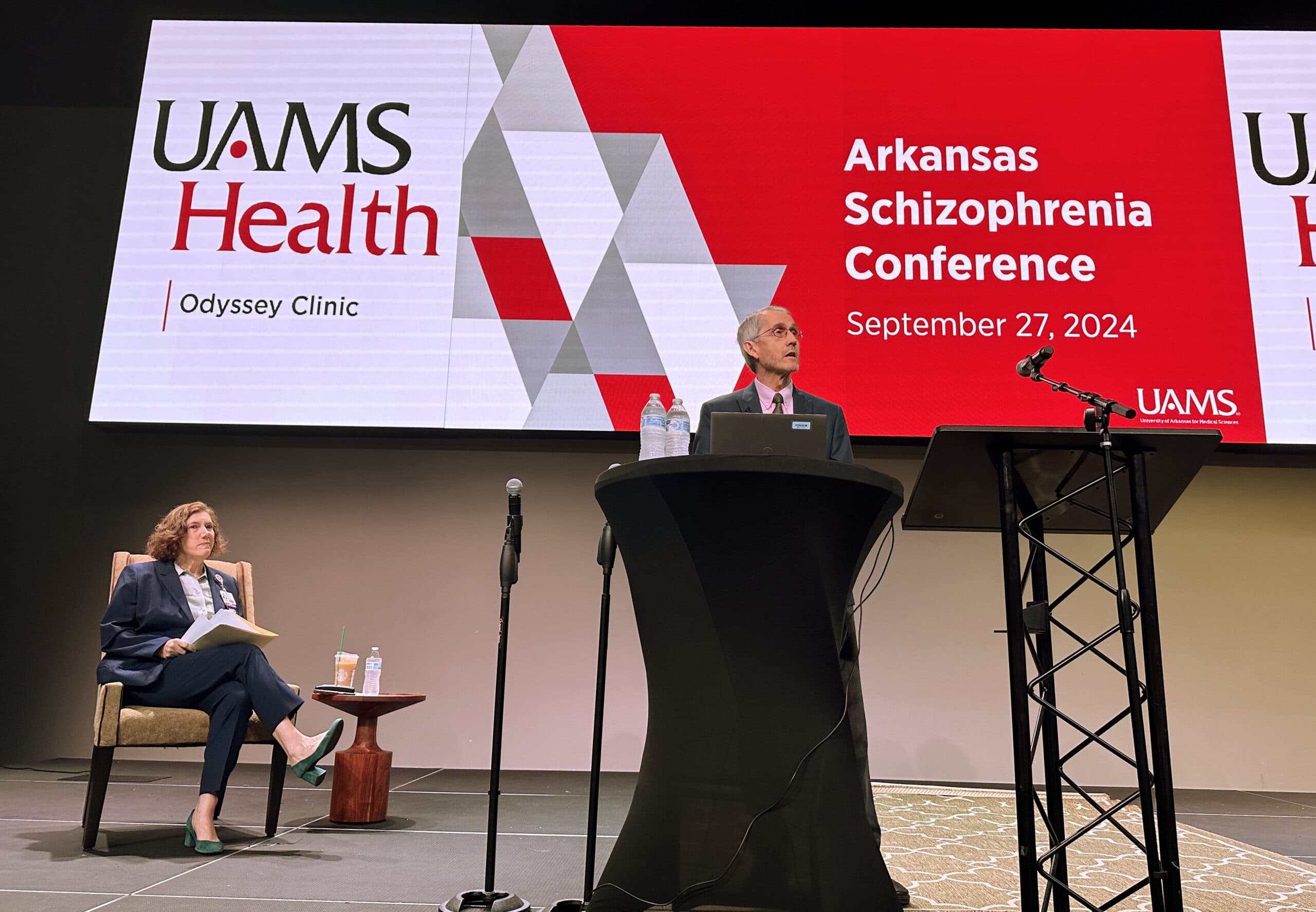

Brian Kirkpatrick, M.D., discusses some of the misconceptions about schizophrenia at the Arkansas Schizophrenia Conference.

Image by Tim Taylor

Schizophrenia Conference Offers Education, Optimism

| The more than 250 people who attended the Arkansas Schizophrenia Conference, hosted by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences’ Psychiatric Research Institute, left the Sept. 27 event with information about the latest treatment approaches and promising findings.

With an audience of clinicians, therapists and support staff as well as law enforcement officials and family members of people diagnosed with schizophrenia, the event, held at the City Center in Little Rock, offered insight into a mental disorder that’s often misunderstood and misdiagnosed.

Deanna Kelly, Pharm.D., BCPP, discusses the future of medications used to treat schizophrenia.Tim Taylor

UAMS Chancellor Cam Patterson, M.D., MBA, welcomed attendees to the conference, while Laura Dunn, M.D., director of the Psychiatric Research Institute and chair of the Department of Psychiatry, recognized the conference participants and organizers.

Brian Kirkpatrick, M.D. MSPH, cleared up several misconceptions about schizophrenia and the people diagnosed with it. His “Schizophrenia 101” focused on the fundamentals of the disorder — symptoms like delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech and catatonia — as well as issues preventing patients from seeking treatment.

“Not everybody has all of these symptoms. The diagnosis is different for every person,” said Kirkpatrick, who explained that environmental factors like respiratory illnesses, low birth weight, childhood abuse and adolescent marijuana use have all been found to be contributing factors to schizophrenia, “which doesn’t go away when you stop using marijuana.”

Despite what many think, people with schizophrenia can benefit from things other than medication, said Kirkpatrick, with many patients relying on learning strategies to help control their symptoms. He recalled one patient that let her dog assist her when dealing with possible delusions.

“She let her dog drive. When she took her dog for a walk and thought she saw something, if the dog didn’t see it, she knew that she could ignore it.”

A combination of therapies and the involvement of the patient’s family and friends can help people with schizophrenia manage their problems, he added. “Ideally, the person with schizophrenia, that person’s loved ones, and clinicians working together can help find the strategies that work best. Most people with schizophrenia can have lives with meaning. There’s hope.”

Deanna Kelly, Pharm.D., BCPP, the acting director of the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Psychiatric Research Center, discussed the evolution of schizophrenia medications, which she called the “cornerstones of treatment.”

Elyn Saks, J.D., Ph.D., gives a first-hand account of living with schizophrenia at the conference.Tim Taylor

The typical antipsychotic acts primarily through blocking dopamine, a neurotransmitter believed to be elevated in patients with schizophrenia, said Kelly.

“It’s a messenger to the brain, and we think that there may be too much dopamine in certain areas of the brain. That’s why we have to block it,” said Kelly, who pointed out that antipsychotics are good at reducing psychosis symptoms but their side effects, weight gain, low blood pressure and sedation, lead many patients to refuse to take the drugs.

Kelly said the approval of a new drug, known commercially as Cobenfy, was announced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration a day earlier, noting that it has shown to have fewer side effects and less negative experiences for patients.

A study of schizophrenia patients showed that only 28% of patients experiencing side effects from their medications will report them to their physician, said Kelly.

“We have to do better than that and that’s why we are seeking new treatments.”

Kim Mueser, Ph.D., a professor at the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation at Boston University, dedicated his portion of the conference to evidence-based practices like family psychoeducation and social skills training. Even with decades of research to support their use, limited access hampers the use of such evidence-based practices. Mueser challenged stakeholders at all levels — patients, family members, clinicians, administrators and policy makers — to address the issue.

Elyn Saks, J.D., Ph.D., director of the Saks Institute for Mental Health Law, Policy, and Ethics at the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law, was diagnosed with schizophrenia at the age of 28. A graduate of Yale Law School and the recipient of numerous honors, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, read excerpts from her 2007 memoir, “The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness,” at the conference and answered questions from the audience.

“I have lived with schizophrenia for almost 50 years,” Saks said. “I have spent hundreds of days in psychiatric hospitals. I was given a quote, ‘grave prognosis.'”

“Good treatment has kept me alive,” Saks said, adding that she was “especially excited” to hear about the opening of UAMS’ Odyssey Clinic, located in the Psychiatric Research Institute, which treats patients 16 years or older who have had psychosis symptoms for less than two years. A second Odyssey Clinic is scheduled to open in Fayetteville in December.

Saks’ long struggle with schizophrenia and a medley of medications and physicians led her to become a staunch advocate for mental health.

“Your illness is part of you. You don’t have to like it, you probably don’t like it, but I urge you to get to know it,” Saks told the audience. Thanks to her medications, “I don’t have no symptoms, but I have fewer than I ever did. Ironically, the more I accepted that I had a mental illness, the less it defined me.”

Funding for the conference was provided by a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) administered by the Arkansas Department of Human Services.