Young Woman Manages Rare Blood Disorder with Help of UAMS

| For about six years, Megan Parrish didn’t know what was happening to her own body.

The teenager would miss school and outings with her friends due to bouts of extreme nausea, pain and dizziness. Her behavior also changed, although she couldn’t pinpoint any reason or pattern for the psychological and physical symptoms.

“For a while everyone wrote it off as teenage angst, but it was stressful and scary. I was a really sick teenager who couldn’t participate in activities with my friends. It was tough,” said the now 29-year-old Parrish.

After an array of medical tests failed to find a cause for her seemingly unrelated symptoms, Parrish continued to experience bouts of illness throughout her teenage years. Finally, at age 18, a long-awaited answer arrived.

“My doctor started to look at the big picture and decided there could be something that tied all of these things together,” she said. It was then that he was able to confirm Parrish was living with a rare blood disorder known as acute intermittent porphyria (AIP).

“Just having a name for it was a relief,” she said.

According to the National Institutes of Health, porphyrias are rare disorders in which the body fails to produce the enzyme needed for the production of hemoglobin in red blood cells. Because hemoglobin carries oxygen from the lungs throughout the body and helps the liver function normally, a deficiency can affect a person in multiple ways.

While there are several types of porphyria with differing symptoms, AIP is known to cause everything from abdominal pain and vomiting to hallucinations and muscle weakness. It is usually passed genetically from parent to child.

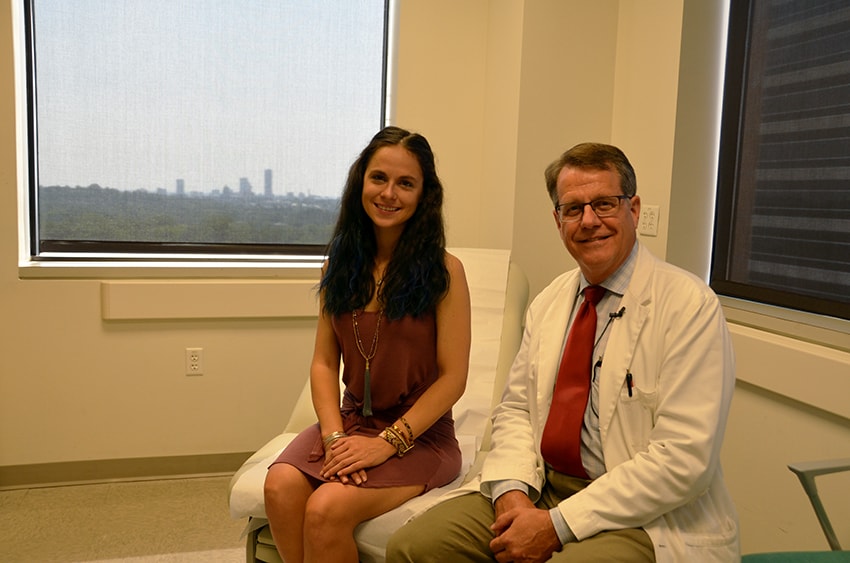

“Although AIP is the most common type of porphyria, it is still rare,” said Peter Emanuel, M.D., a hematologist and professor of medicine in the UAMS College of Medicine. “It is often misdiagnosed and can be challenging to treat,” he added. The exact rate of porphyria cases is unknown, in part because its physical, neurological and psychiatric symptoms mimic other more common conditions.

After her diagnosis was confirmed, Parrish was referred to UAMS for specialized treatment. Soon afterward she met Emanuel, who developed the treatment regimen she has maintained for the past 10 years.

“Because AIP is intermittent, Megan goes through good cycles and bad cycles. We adjust her treatments and clinic visits to meet the needs she has at the time,” Emanuel said.

Parrish’s primary therapy involves weekly IV infusions lasting from 60-90 minutes. Although AIP is noncancerous, she is seen in the UAMS Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, where Emanuel serves as director.

In addition to her infusion treatments, Parrish also comes for follow-up visits every four to six weeks during good cycles and more often when her symptoms flair up.

“When I’m in the midst of an outbreak, I can experience anything from mild nausea to pain that feels worse than a broken bone. Sometimes I will have insomnia for days. Thankfully, I’ve been on an upswing this year and have been having fewer incidences. It’s easier to manage when I listen to my body,” she said.

Although AIP is incurable, research is underway to discover new treatment methods for people with the disease. Parrish is hopeful that a clinical trial will soon be available at UAMS that could offer her the latest therapies before they are widely available.

She also is thankful to live near UAMS where a specialist is just minutes away.

“I can’t say enough good things about Dr. Emanuel. He makes me feel like a part of the treatment process. I’m lucky to be here,” she said.