High-Tech Gait Lab Maps Infant Biomechanics

| Feb. 8, 2018 | Modern babies move from car seat to stroller to baby swing and back again. Meanwhile, what they aren’t moving is their muscles.

What effect does all of this containment have? What muscles are key as babies work toward developmental milestones? How can baby products have an impact – for better or worse?

These and other questions are the focus of research for Erin Mannen, Ph.D., a mechanical engineer who joined the UAMS faculty in mid-2017 to lead biomechanical studies of the spine, bone and joints. She is an assistant professor in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery in the UAMS College of Medicine.

“Biomechanics is essentially the study of the body in motion,” Mannen said. “We are looking at infant muscle and motion activity in various positions to get a baseline understanding of how infants are using their muscles in common positions. We want to understand optimal positioning to prevent musculoskeletal problems or motor development delays.”

Mannen is conducting her research with the help of the high-tech gait and motion-detection laboratory at the HipKnee Arkansas Foundation in Little Rock, using technology that fills an entire room. Special cameras at strategic points along the walls create a 3D capture zone. The research subject wears markers that are tracked by the cameras and recorded by the computer software.

“We are able to see how nearly every part of the body is moving,” Mannen said. “We can measure how people move using the cameras, how they load their joints using force plates embedded in the ground, and how their muscles are activating using electromyography.”

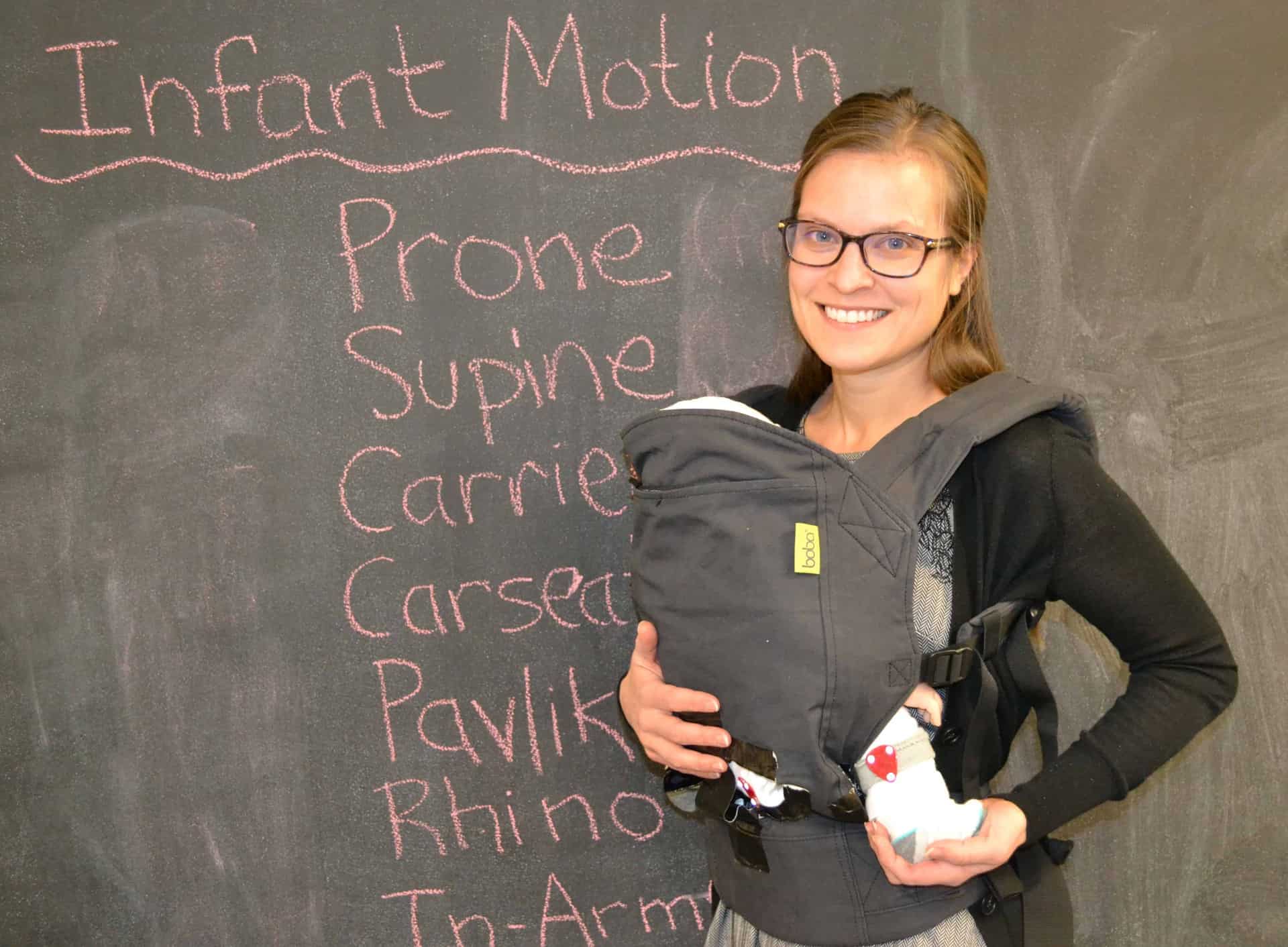

Mannen’s research is already being noticed. Two previous – but connected – studies are in the process of being published. Those studies looked at the biomechanics of adults while they carry babies in “babywearing” carrier devices.

How knee replacements affect golf swing is one of several studies at the HipKnee Arkansas Foundation, the high-tech gait and motion-detection laboratory used by the UAMS Department of Orthopaedic Surgery.

Now, Mannen is looking at babywearing’s effect on the babies. Specifically, she wants to know if infants with hip dysplasia can safely spend time in babywearing carriers. It’s also possible that babywearing could have a similar therapeutic impact for babies as the more unpleasant orthopaedic devices that are now standard practice.

The International Hip Dysplasia Institute (IHDI) has featured her work on its website and has provided a $10,160 grant toward the promising research, which is also being funded by a $31,724 grant from Boba Inc., which makes babywearing products.

“It is hypothesized that wearing an infant inward facing in a structured baby carrier results in similar muscle activity and hip positioning as the orthopaedic devices currently used to treat babies with hip dysplasia,” Mannen said. “Appropriate babywearing has the potential to offer parents of hip dysplasia patients a ‘break’ from the cumbersome orthopaedic devices, allowing them to experience the many benefits of babywearing while not endangering their baby’s hips.”

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery Chairman C. Lowry Barnes, M.D., said research is an important part of the department’s mission.

Electromyogram testing – to detect muscle activity – is one of several technologies in use at the gait and motion-detection laboratory that allow researchers insight into human movement in a variety of contexts.

“By researching the structure and function of human movement in a variety of contexts, the goal is to improve the development and assessment of orthopaedic interventions and better understand injury prevention,” Barnes said. “Having researchers like Dr. Mannen on our team not only furthers medical knowledge, but has the potential to inspire students to be the kind of innovative thinkers they need to be and directly impact patient care.”

Mannen became interested in this line of research as a new mother. She used a babywearing carrier to soothe her first child, who was colicky and had trouble sleeping. While the emotional benefits of babywearing are well-established in the medical literature, she found the biomechanical research lacking.

Similarly, as she learned about how to safely put her baby to sleep on its back to prevent Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), she also learned that preliminary research had indicated this sleeping position – while excellent at reducing the rates of SIDS – combined by a general lack of “tummy time” for babies had reduced the development of muscles in babies’ necks and upper backs. She wanted to learn more.

While the babies were hooked up to the sensors during the tummy time research, she happened to watch their biomechanics and muscle firing as they rolled over. She looked to the established research on such developmental milestones for infants and found it lacking. The biomechanical changes behind rolling over, crawling and other milestones will likely be her next research pursuit.

“Often the inspiration for research comes from personal experience,” Barnes said. “That’s one of many reasons I’m proud of the diverse team we have in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery. Everyone brings something a little different to the table, and they are encouraged to bring their interests to bear, whether it’s for research or finding novel ways to serve our patient communities.”

In other research at the gait lab, Barnes is studying how joint replacements affect golf swing in athletes. Simon Mears, M.D., Ph.D., is studying safe yoga practice in hip and knee replacement patients.

“With this technology, we are limited only by our imaginations,” Mannen said.