Recent Discovery Brings Storied Composer Back into the Spotlight

| March 1, 2018 | Florence Price has always been the same accomplished composer worthy of immense respect for her contributions to classical music, but her posthumous recognition has waned for nearly the entirety of the 65 years since her passing.

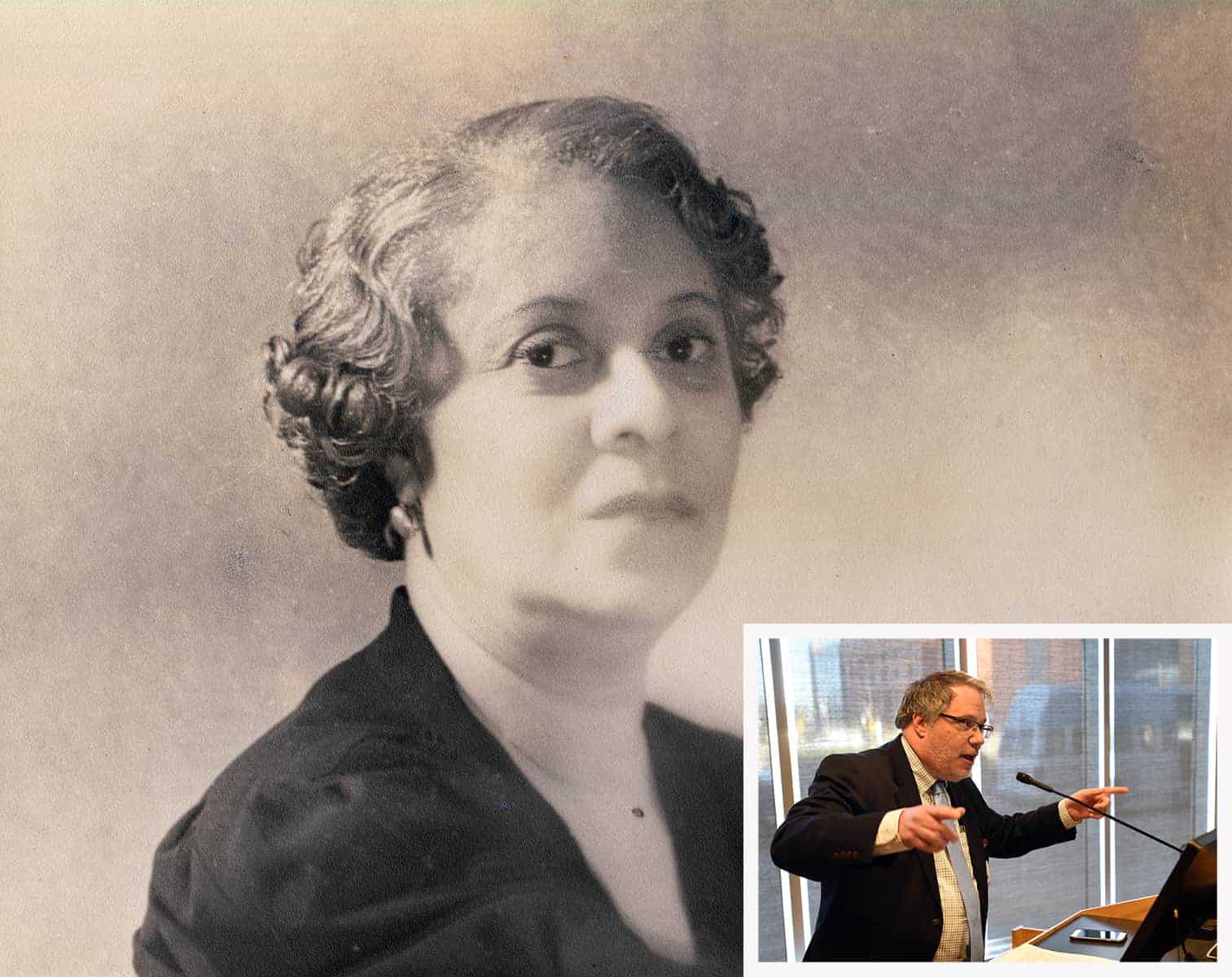

Price, a native Arkansan who died at 66 in 1953, was the first African-American female to have a composition played by a major orchestra. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra bestowed her that honor when it played her Symphony in E Minor on June 15, 1933. She enjoyed noted appreciation during her lifetime and collaborated with prominent artists such as Marian Anderson and Langston Hughes.

However, that prominence faded after her death as most of her work was feared lost. Deservedly, the recognition of her contributions has been rekindled in recent years following an unexpected treasure-trove of findings at the composer’s former weekend home in St. Anne, Illinois.

“There are many amazing African-Americans who have contributed a lot to where we are as a society and she’s one of the hidden figures,” said Billy Thomas, M.D., M.P.H., vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion and director of the UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs, to an audience of UAMS faculty, staff and students Feb. 26.

Billy Thomas, M.D., M.P.H., vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion and director of the UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs.

Tim Nutt, director of the UAMS Library Historical Research Center, recounted Price’s life and the discovery of her lost and unknown works that he helped unearth at an event honoring Black History Month, hosted by the UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs, Chancellor’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee, UAMS Library and UAMS Historical Research Center.

Price was born in Little Rock in 1887 to James H. Smith, a dentist, artist and published author, and Florence Gulliver Smith, a pianist and teacher. She graduated valedictorian from Capitol Hill School in 1903, then, studied at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. While there, she began to publish and sell some of her compositions.

Following her studies, she returned to Arkansas where she would teach in Cotton Plant and at Shorter College in Little Rock. She also briefly taught at Clark University in Atlanta. All the while, she continued to compose countless pieces.

She married Thomas Jewell Price, an attorney, in 1912. The couple had three children and remained in Little Rock until the lynching of John Carter in 1927 when several African-American families became distraught with the killing and left.

The Prices moved to Chicago, where her father had a dentist office after the Civil War and prior to coming to Arkansas. The Great Chicago Fire in 1871 destroyed his practice.

Price, photographed here in her St. Anne home, works on a piece at the piano. Photo Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries.

Price’s reputation and prominence blossomed while in Chicago. In 1932, she submitted works for the Rodman Wanamaker Foundation awards and won for her Piano Sonata in E Minor and her Symphony in E Minor, which was played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra a year later.

Marian Anderson performed one of Price’s songs “My Soul’s Been Anchored in De Lord,” at an open-air concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1939. Anderson’s concert, offered to her after she was denied permission to sing in Constitution Hall, was widely attended by more than 75,000 people on Easter Sunday.

Price died June 3, 1953, and the memory of her work began to fade. It would be 56 years before a chance discovery by an Illinois couple would breathe new life into Price’s work. The couple had recently purchased the dilapidated former weekend home of the Prices and begun renovation when the discovery was made.

Following a little research, the couple contacted the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, which already housed a small collection of Price’s works. Nutt, who worked in the University Archives’ Special Collections at the time, made the trek to St. Anne, Illinois, with a fellow UA archivist to determine the state of her works, which had sat abandoned for decades.

The yard surrounding the bungalow was overgrown with tall grass, weeds and numerous trees. The house itself was vandalized and held extremely worn and tattered furniture, gaping holes in the ceiling and sunken floors. Price’s prized works lay scattered on the floor — thrown from their filing cabinets by vandals — in a room with an unceremonious skylight as result of a fallen tree, vulnerable to the elements. Miraculously, the papers were in good condition.

“It’s a wonder anything survived in that house,” said Nutt. “A few papers were mildewed or molded but for the most part, they were in extraordinarily good condition.”

Nutt said he knew he and his fellow archivist had made a considerable discovery, but they were not aware of how immense it would be. There were lost works and unknown pieces, as well as previously unseen family photos, a painting of her father’s, and manuscripts of his novel, Maudelle, published in 1906.

“It was an exciting find,” said Nutt.

With the discovery has come national attention for Price, including from The New Yorker, The New York Times and NPR.

Er-Gene Kahng, a violinist and Graduate Studies Chair in the University of Arkansas’s J. William Fulbright College of Arts & Sciences’ Department of Music, recorded some of Price’s found compositions, including Violin Concerto No. 2. She played a recording of the 15-minute piece for the audience at UAMS.

“I came to see the piece’s theme of a dream not yet realized,” said Kahng. “The theme is in a remote key so it is a jarring experience, yet it’s sweet and distant. It’s a musical personification of the tensions and unrealized dreams Florence undeniably experienced in her lifetime and she’s expressing it in her music.”

Kahng said her realization brought feelings of empathy and compassion for Price’s struggles.

“She writes in many letters and describes her race and gender as two handicaps,” said Kahng. “It’s absolutely heartbreaking to read these letters and I can only imagine this was at the forefront of her mind, so how could it not show up in her music?”

Er-Gene Kahng, Graduate Studies Chair in the University of Arkansas’ J. William Fulbright College of Arts & Sciences’ Department of Music, said she was taken by the originality in Price’s compositions.

Kahng was amazed by Price’s originality, as well as her commitment and meticulous attention to detail in order to honor the tradition of classical music in her pieces, yet find a way to make them her own.

“When you’re tasked with creating something original, the knee-jerk reaction is to abandon pre-existing systems and forge your own path,” said Kahng. “That can be interesting, but more incredible is to inherit and absorb the tradition and insert pockets of originality and recreate the system.”

Kahng said she’s hopeful this resurgent adoration for Price’s work will continue to gain.

“It’s been encouraging to see so much interest,” she said. “Speaking with historians and scholars who have researched her since the 1970s, it’s been a warm and enthusiastic response. It’s my hope she is on her way to becoming a normal part of the concert stage and a normal part of the discussion on classical music.”